Introduction

Antonín Dvořák moved to the United States in December of 1892 only to return back to his homeland of Bohemia 3 years later. Yet, in those 3 years, he wrote 3 of his most popular pieces: the American String Quartet, the Cello Concerto, and his 9th symphony title “From the New World”.

In Dvořák’s own words, the real meaning of the title is

“Impressions and greetings from the new world”.

“From the New World” was written by Dvořák himself as a joke before sending the autograph to his editor.

It is often said that the “American” aspect of this music comes from the fact that Dvořák embraced the American idioms (musical idioms) infusing his compositions with them. While that is partially feasible, it also poses the question of “what is American music?”, something that Leonard Bernstein brilliantly, as usual, addressed in one of his legendary lectures.

While most American composers of the time considered American folk music somewhat of second rate music, Dvořák went in the exact opposite direction. Faithful to his love for folk music he mixed and matched the “primitive” sound of American folk tunes with the old European symphonic form, creating something that captured people since its premiere.

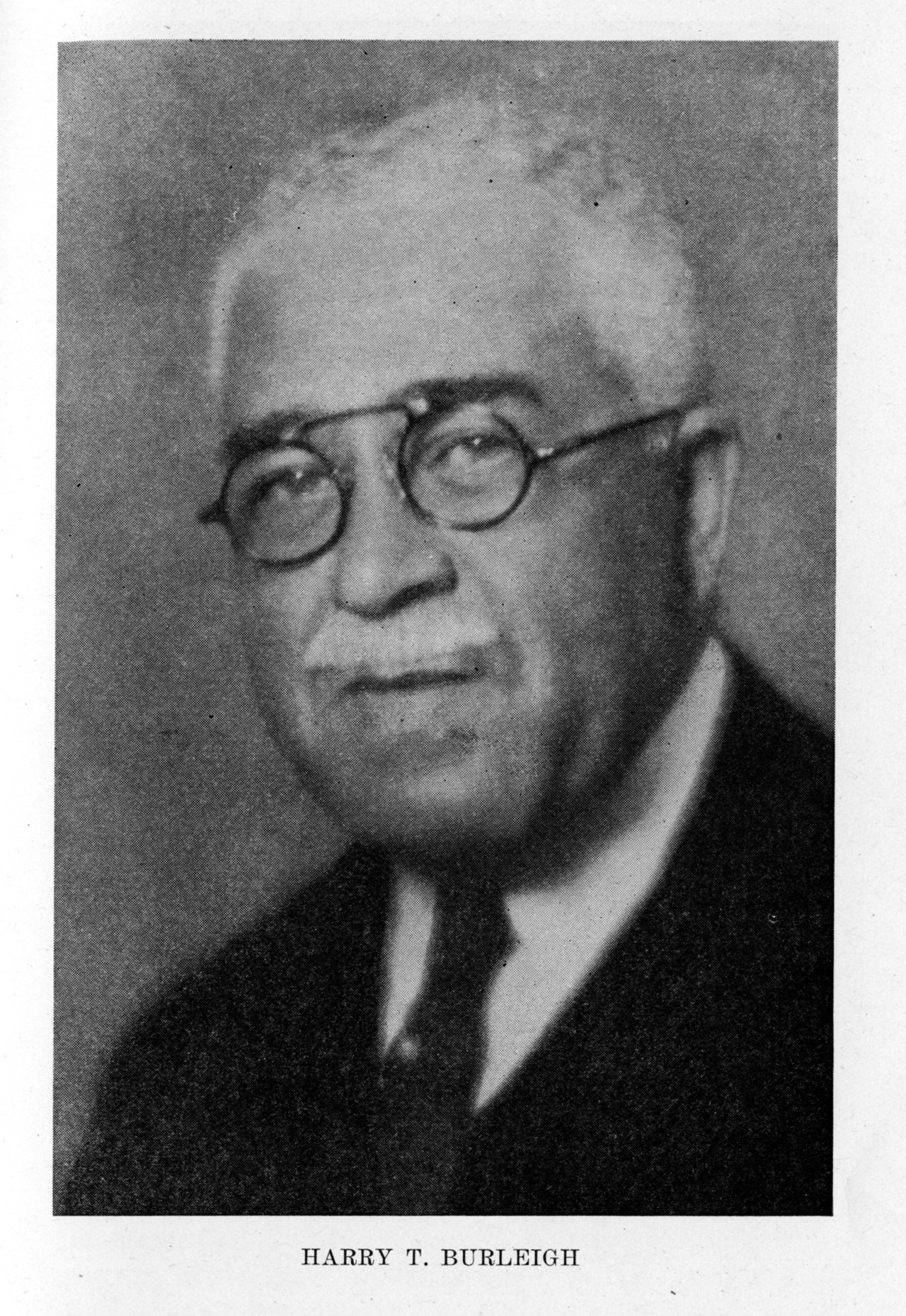

But how did Dvořák get acquainted with these folk melodies and rhythms? Legend wants that while walking down the hall of the National Conservatory of Music in New York, of which he had accepted to be the director, he heard a young black student singing, while he was working as a janitor to help to pay the costs of his education.

Dvořák was struck by his voice but most importantly by the song he was singing. From then on, the student, whose name was Harry Burleigh, sang for him many times, and Dvořák immersed himself in the warmth of the negro spirituals.

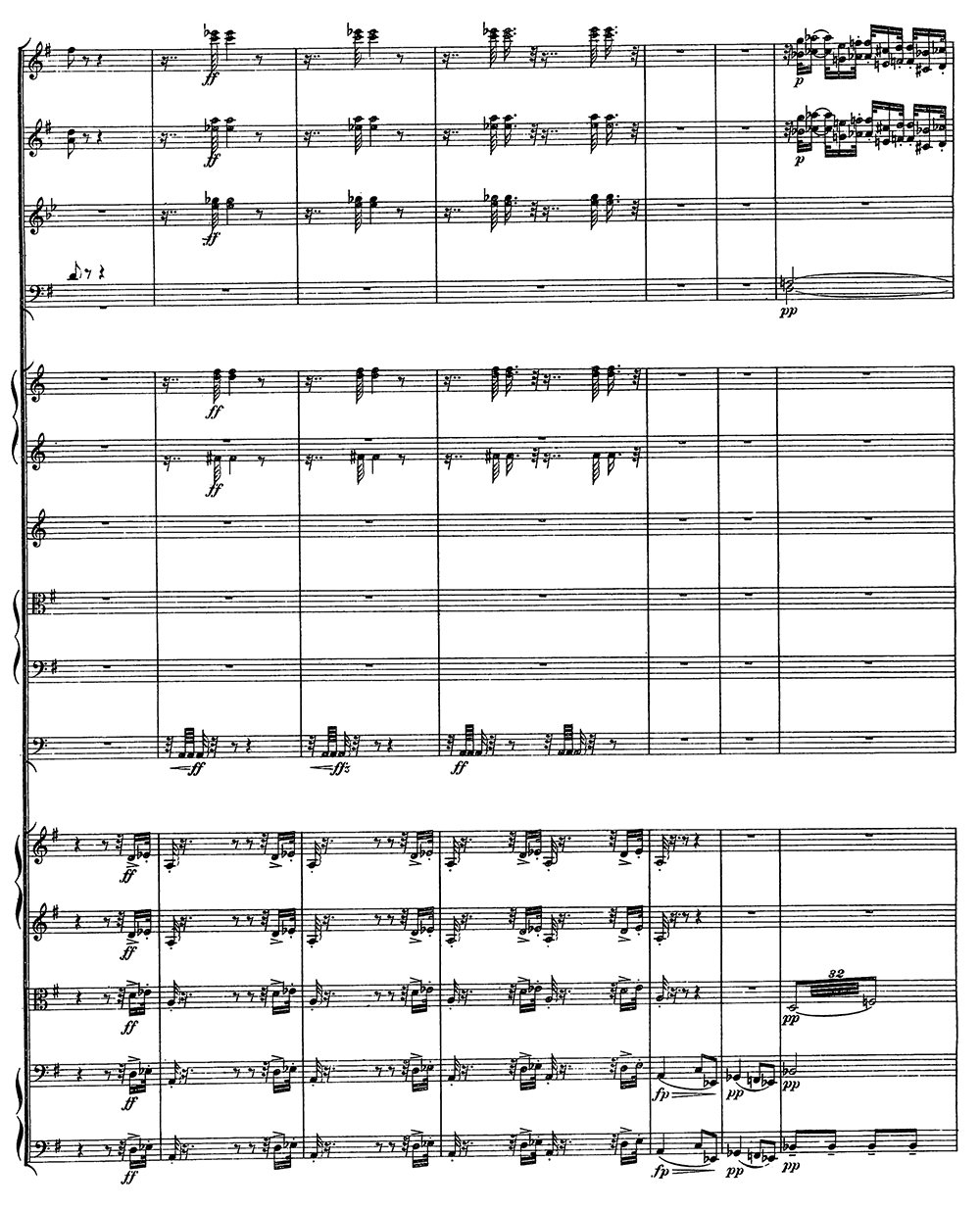

As much as this symphony is imbued with these tunes it remains as classical as it gets in terms of structure. The first movement is in a typical sonata form, with a slow introduction and an Allegro, an exposition with a first and second theme, a development, a recapitulation, and a coda.

Exposition

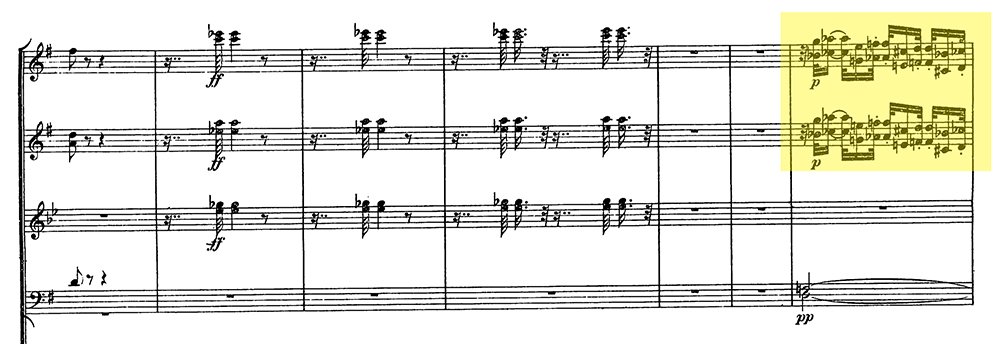

Adagio

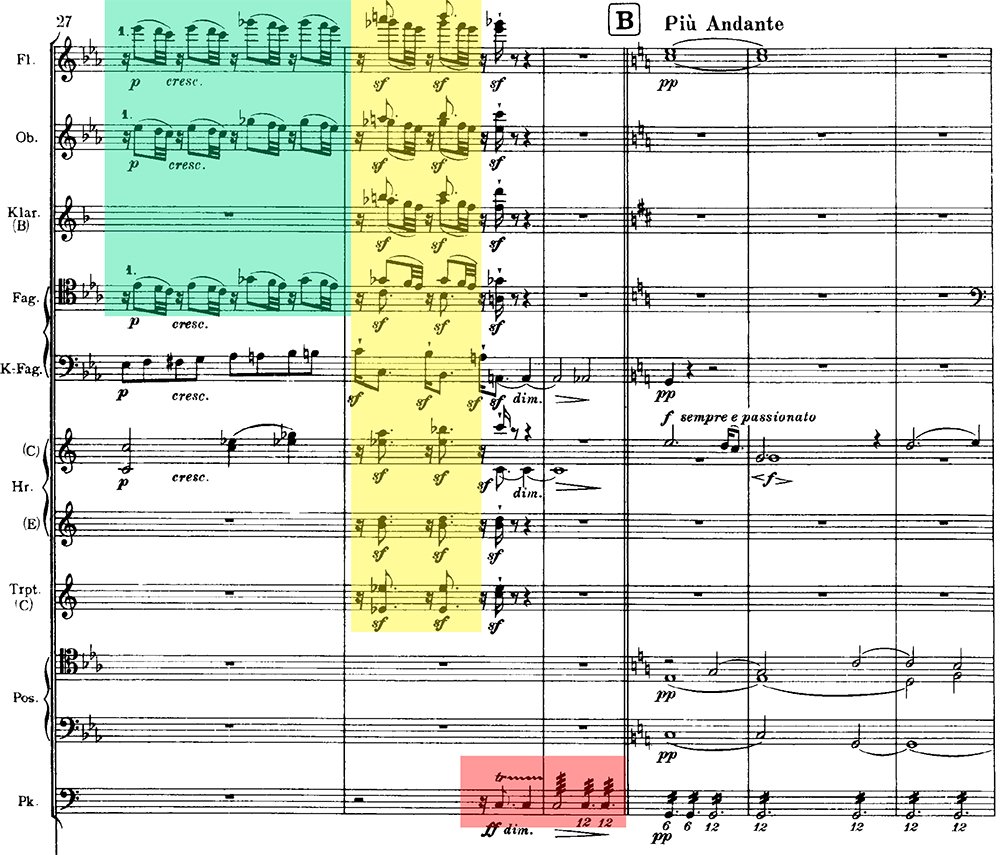

As much as he loved America, Dvořák always longed for his homeland: the opening of the symphony presents exactly that in its slow longing theme

interrupted almost immediately by a calling of 2 horns. The scene repeats, changing color from the lower strings to the higher woodwinds, but this time, instead of the horns, we have a shocking and violent explosion of the orchestra.

Technical tip

It’s an unexpected moment of very high energy, something the audience of the time would have not expected. As conductors, we should try to preserve the surprise effect by avoiding big and obvious gestures, opting for a more focused and tight stroke, right in front of the body.

This surprising moment lets us know that the quiet is already gone. The syncopations of the woodwinds introduce the thematic cell, based on the pentatonic scale, that will be the base for the entire movement.

Many people have pointed out that this is the first hint towards American folk music, in virtue of that same pentatonic scale, largely used by traditional American music. However, the pentatonic scale had already been in use in many other parts of the world. Without going too far, in Bohemia for example, Dvořák’s home country. Not to forget that Debussy, in the same period, had started toying with it drawing inspiration from the Indonesian Gamelan orchestra he had listened to in Paris.

This introduction ends with a succession of syncopations, diminished seventh and timpani strikes that are remarkably similar to the end of the introduction of the last movement of Brahms’ first symphony. And, as we know, Brahms was one of the first to endorse Dvořák’s compositional genius.

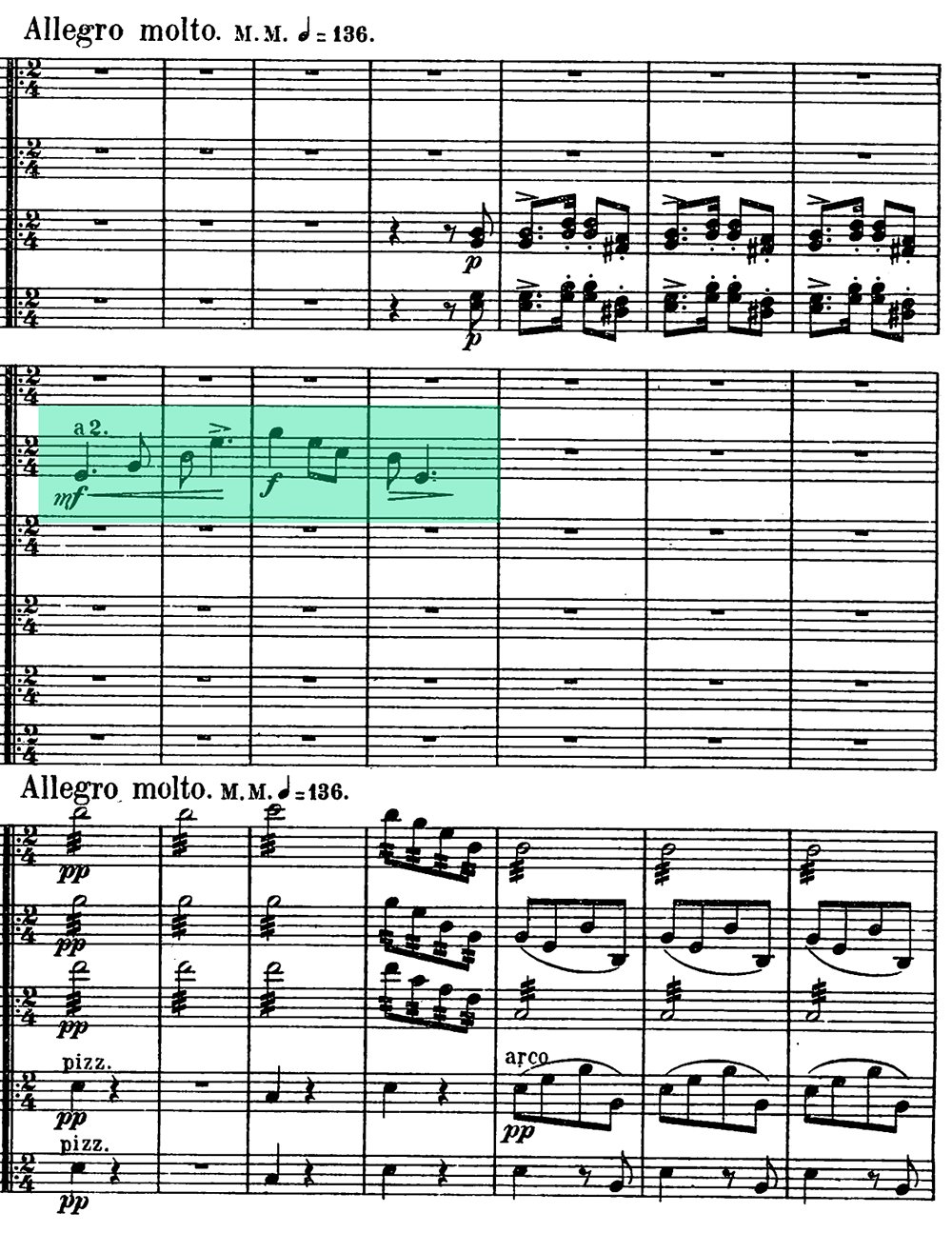

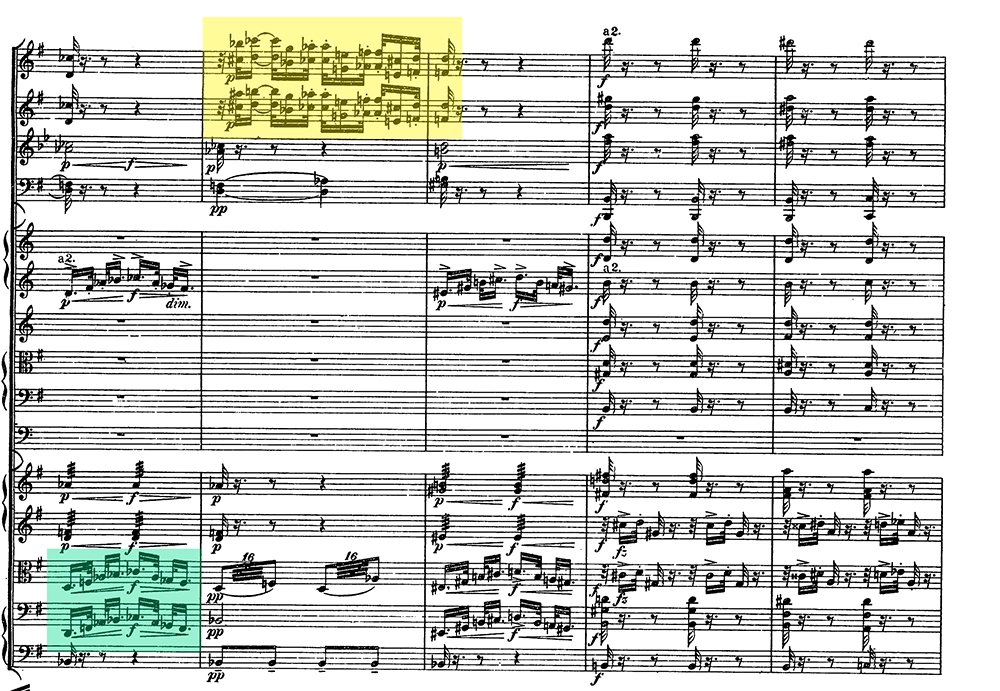

Allegro molto

First theme

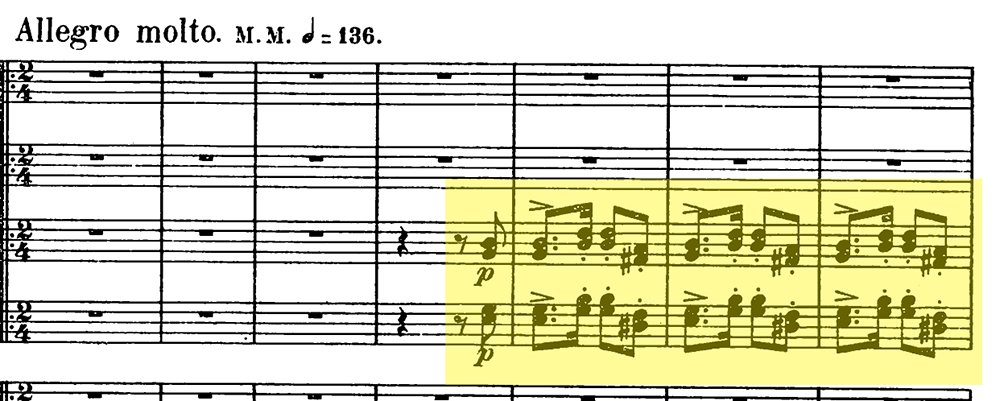

We’re driven into the Allegro where the first theme is rich of the typical Dvořák’s melodic invention, played by those same 2 horns that had that “calling” moment in the very beginning (the third and fourth horn) and then flowing naturally from one section to another

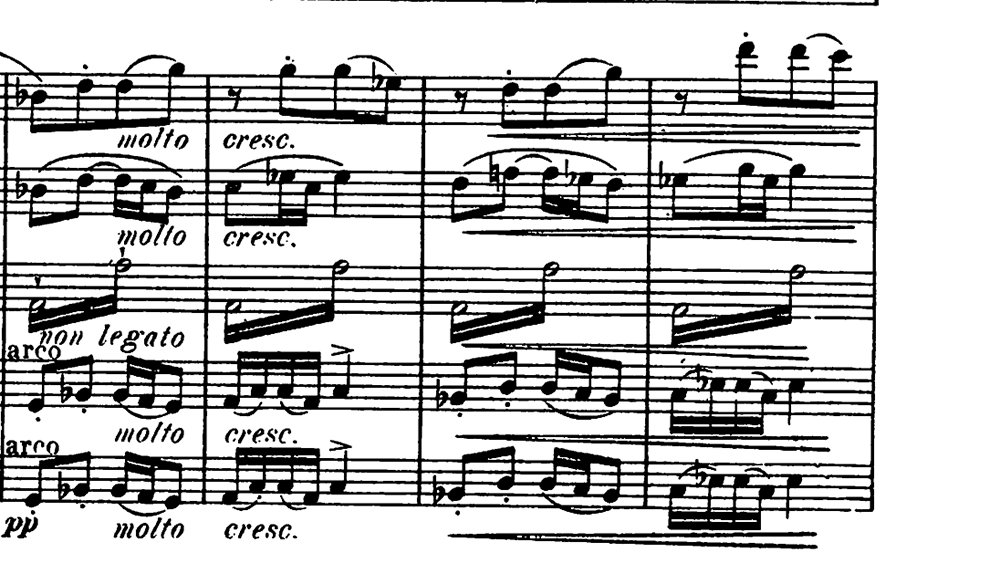

We drive into an explosion of energy: the first theme is played by the bassoons, trombones, and 2 horns, on top of cellos and basses while the rest of the orchestra responds with the rhythmic elements.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Second theme

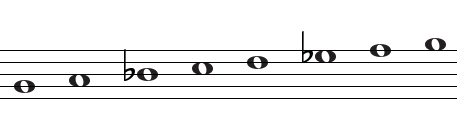

Here comes another theme often referred to as purely native-American. Certainly one can understand why by looking at the way it is constructed: a modal scale (aeolian in this case) on top of a pedal in fifth.

However, there are some problems with this idea: first, Dvořák had never met any native Americans (at least that we know of) and we are not really sure how much he could identify as Native-American versus African-American. Tunes had not been transcribed and catalogued yet which certainly blurred the contours of different folk areas.

Secondly, the use of mode, however associated with some folk and Native-American music, had been used in Gregorian music, medieval, as well as Greek and Hindu.

Nonetheless, the inventiveness of this theme is extremely evocative but as it happened for the first theme Dvořák ramps up the energy almost immediately, using first the entire thematic cell

Third theme

As per tradition, we would expect the end of the exposition but Dvořák breaks off a bit by introducing a calm and relaxed third theme, perhaps inspired by a spiritual called “swing low sweet chariot”. The resemblance is remarkable, especially if one takes it from “chariot” on but Dvořák always insisted that it was only a resemblance in the use of the pentatonic scale and nothing more.

Technical tip

Register the flute line with your left hand: it will make a connection (visually as well) tying it to the first violins at the end of the phrase, for which your hand will be in the optimal position.

Although very far away in character from the first theme, this third theme is almost exactly the same rhythmically, building an ideal bridge between the two and giving cohesiveness to the whole movement.

Before going into the development there is a repeat mark which I firmly believe should be observed: there’s so much thematic material in the exposition that to me it really makes sense to hear all of it again. And even though this symphony is more than 100 years old and many know it by heart, there will always be someone who is listening to it for the first time.

Development

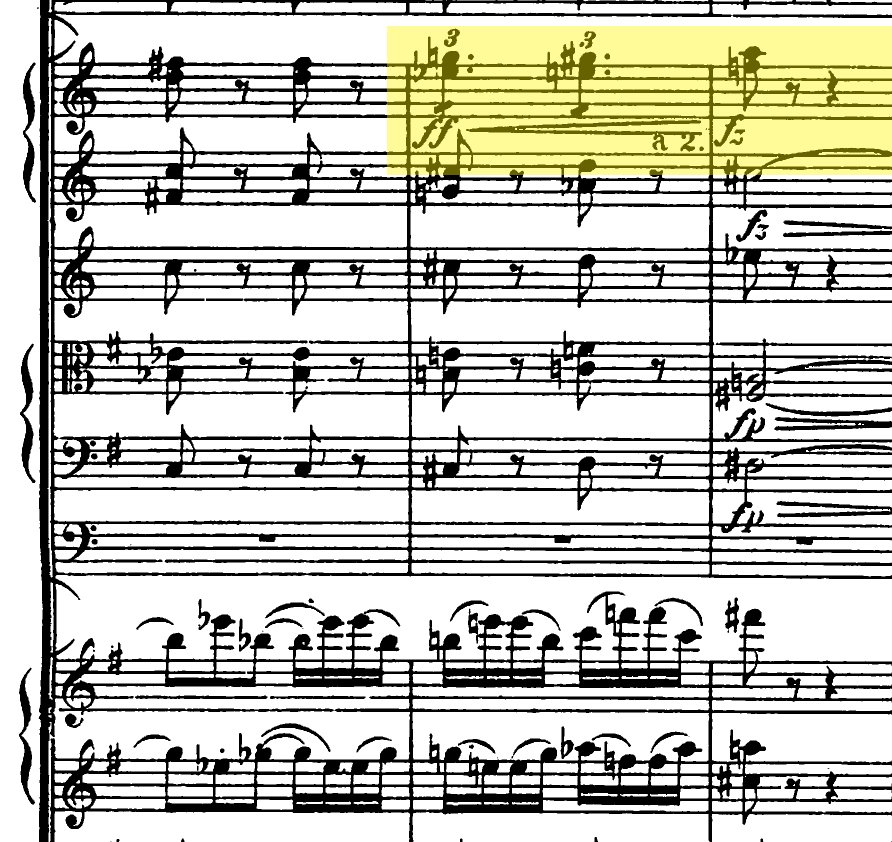

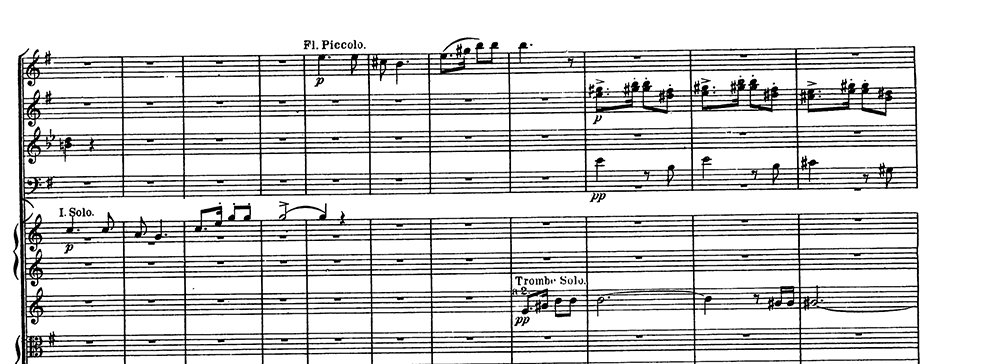

The same third theme we just left is picked up by the horn solo and then by a piccolo, echoed by the trumpets: it’s an extraordinary moment of transformation of sound where we see the music material molded into something different

Technical tip

Initiate the sonority and then let it be, without insisting, otherwise, the sound will get harsher and harsher, especially from the brass section.

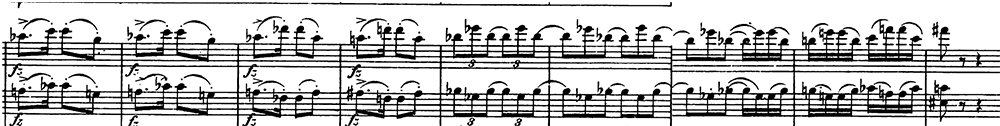

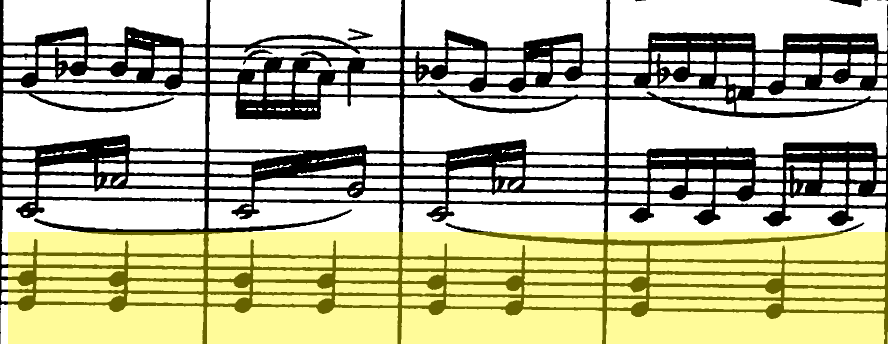

The energy builds up using the same material, in its original form, or in bits of it. Dvořák uses a few composing “tricks” here, all at once: he shortens the values creating a natural accelerando for instance, moving from eight notes to triplets to sixteen notes;

at the same time he moves up of half step at a time, a typical progression that adds intensity and drive;

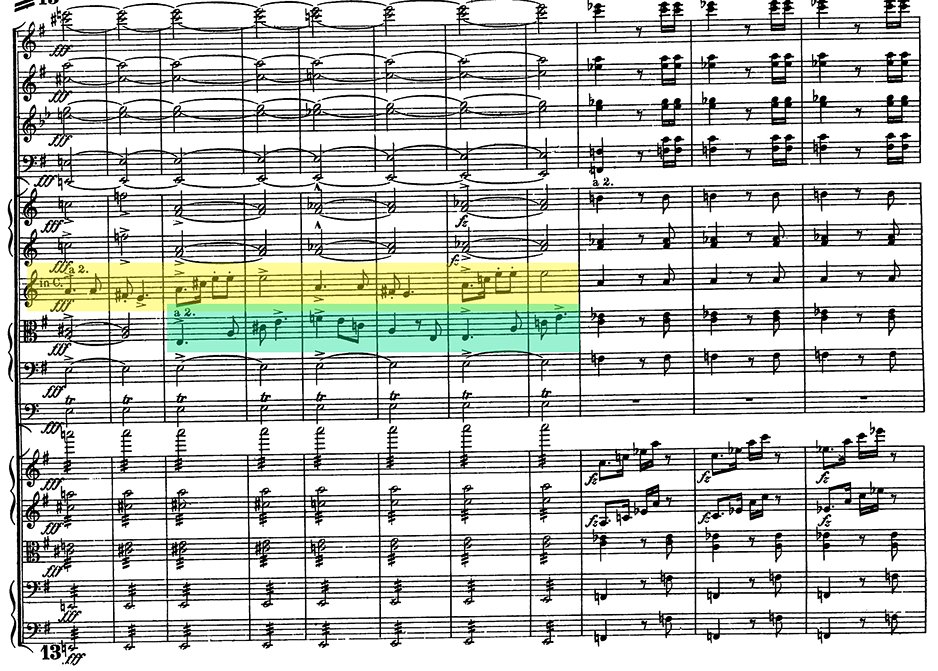

and to top it off, he uses triplets in the horns in crescendo against the quadruplets of the violins, reaching the climax.

At this point, the energy starts to dissipate and within a few bars we are taken into the recapitulation.

Recapitulation

The third and fourth horn expose the first theme once again followed by the oboes and then the strings. But it’s a shorter version of the exposition and we are soon taken to the second theme played in a beautifully soft and warm solo of the second flute. Notice how the sforzandi and the accents are gone.

Technical tip

On bars 358 and following it’s really important to take care of balance, especially in the lower register: notice how the dynamics between cellos and basses are different from one another.

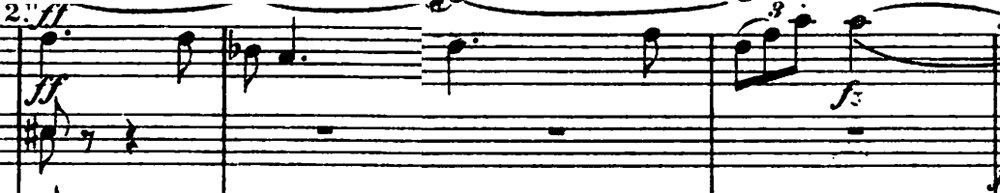

The same second flute is in charge of the third theme as well followed by the violins which in the key of Ab, in which we are now, sound very luminous while maintaining a certain weight in sonority. And after this bucolic moment, we are taken to the coda with a crescendo to a fff.

Coda

Here’s something that truly marks a great composer: the ability to combine all different themes or parts of them transfiguring their original character in the most natural way. Interestingly enough, nothing from those melancholic opening bars of the Adagio comes back in this coda. That calm and relaxed third theme is turned again into something powerful and dramatic counterpointed by the first theme.

That very same first theme is shortened and then presented again, and then stretched all the way to the end, storming through to the last bars where only it’s first rhythmic element is left to close the movement.

In conclusion

Something that I find really useful whether you are studying this piece as a conductor or not, is reading what was another source of inspiration for Dvořák, as he himself pointed out many times: The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. If you read the ending of this poem you’ll also see the ending of the New World Symphony, as well as its beginning: the sorrows of departure, in one way or another, permeate the entire symphony.

0 Comments