Introduction

The symphony n.36 was written by Mozart in only 4 days during a stopover in the Austrian town of Linz. Mozart and his were returning back home to Vienna from Salzburg in late 1783.

In a letter dated October 31st, 1783 Mozart wrote to his father:

“On Tuesday November 4 I will give a concert in the theater, but, not having brought any Symphony with me, I am composing one at great speed, because I have to finish it by this date”

To complete the program of a concert organized by the local count, only an opening piece was missing, so they turned to Mozart.

With it Mozart added to his catalogue a work that takes leave from the world and sonorities of the Haffner’s Symphony. The following three years will be filled with a mysterious silence in terms of composition of symphonies. A silence during which the world of the last 4 symphonies fully matures.

The symphony in G major K444 that normally follows this one as the number 37 is now recognized as having been written by Michael Haydn. Only the introduction is Mozart’s.

Drawing of Mozart in silverpoint, made by Dora Stock during Mozart’s visit to Dresden, April 1789

Mozart – Symphony n.36 “Linz” K425

Should you need a score you can find one here.

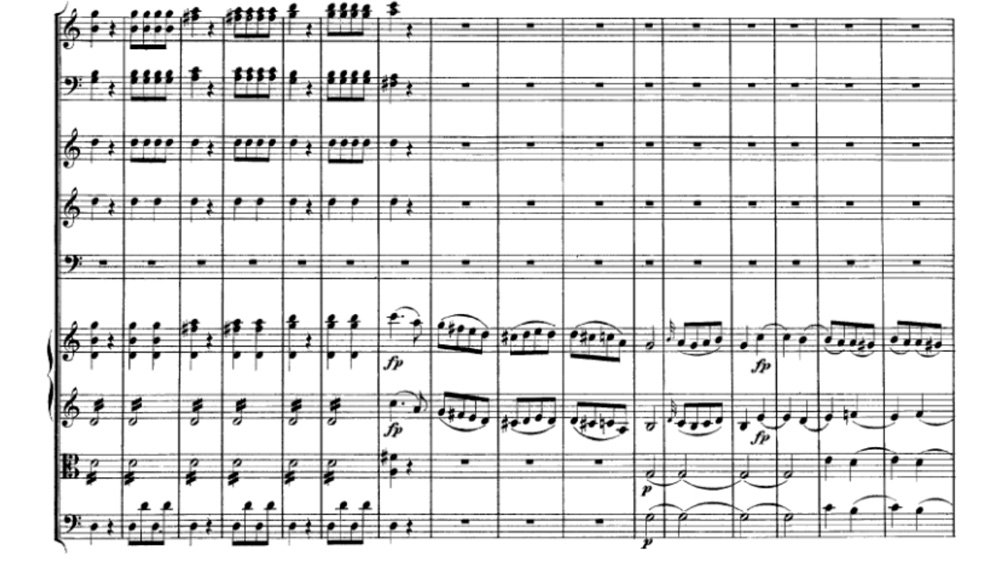

Adagio

As with many symphonies of this period, the Linz opens with a slow introduction. The tempo indication – Adagio – literally simply means “with ease“.

Three bars of powerful chords in full orchestra grab the attention of the listener and change the key right away moving from the starting C major to F major. Notice also one other thing: the flutes are completely missing from the orchestra. This creates, in general, a slightly darker and heavier sound.

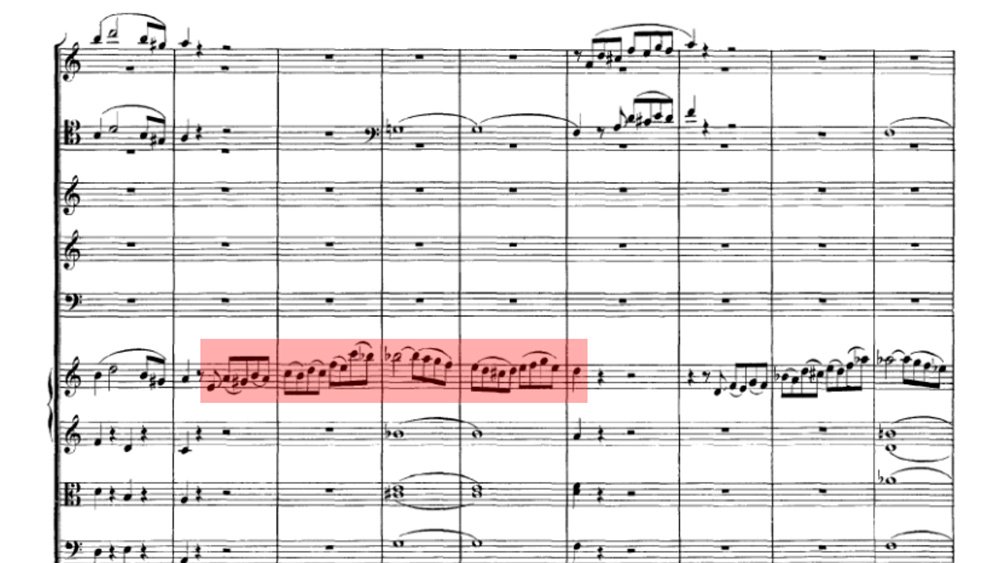

The whole introduction is based on repeating models. The second violins start a phrase on F and raise it to A two bars later. The first violins gently answer with a downward scale, while the rest of the orchestra pulses underneath

The model changes: the accompaniment intensifies, moving from 8th notes to 16th, and the line moves from the bassoon to the oboe, gradually darkening in a series of 9th chords to F minor.

The same line is picked up by the cellos and basses moving to even darker places (and to C minor). And then by the first and second violins, one after the other.

A question and answer moment based on a chromatic scale seems to be closing the introduction in a mysterious way until the last chord – on the dominant of C – brings back the power of the beginning and prepares us for the Allegro.

By the way, the chromaticism in Mozart is something that came up already with the Prague symphony.

Technical tip

The challenge in the first few bars of this introduction lies in switching between subdivided and non-subdivided movements.

To get a broader sound in the initial chords, do not stop the stroke right away but stretch it for the full length of the eight note value.

For a technical analysis, along with some exercises, take a look at this other video

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Allegro spiritoso

Exposition – First theme

First, a note on the adjective of the tempo indication: “spiritoso” means spirited but also funny as in “entertaining“. One of the first things we notice in the construction of the first theme is it’s stop-and-go qualily. It’s unexpected and responds to the nuances of the “spiritoso” adjective.

The motor is provided by the rhythmic motions of the second violins and the couple cellos/basses while the theme goes to the first violins. But after only two bars it comes to a stop as if it was interrupted

The answer is very lyrical. Notice the second violins line, passed to the first and connected by the imitation of the trill element. The forte that comes right after follows the same schema of stop and go with a lyrical answer.

The next forte presents a leitmotiv of Mozart’s music: that “pam-pam-pa-pam-pam” is almost an obsessive rhythm which Mozart makes use of in many of his compositions and is used here to kick off the section of the exposition which will transition to the second theme.

Look at the structure, mathematically classical: 4 bars of C major, moving to the dominant, the 4th degree of the scale, the dominant again, and then back to C. The second time Mozart modulates to G major.

The excitement kicks off. Mozart smartly reuses an element we’ve already heard. Everything clouds for a moment with a small A minor parenthesis. We would expect a second theme here but Mozart lingers a little longer on the same elements

Second theme

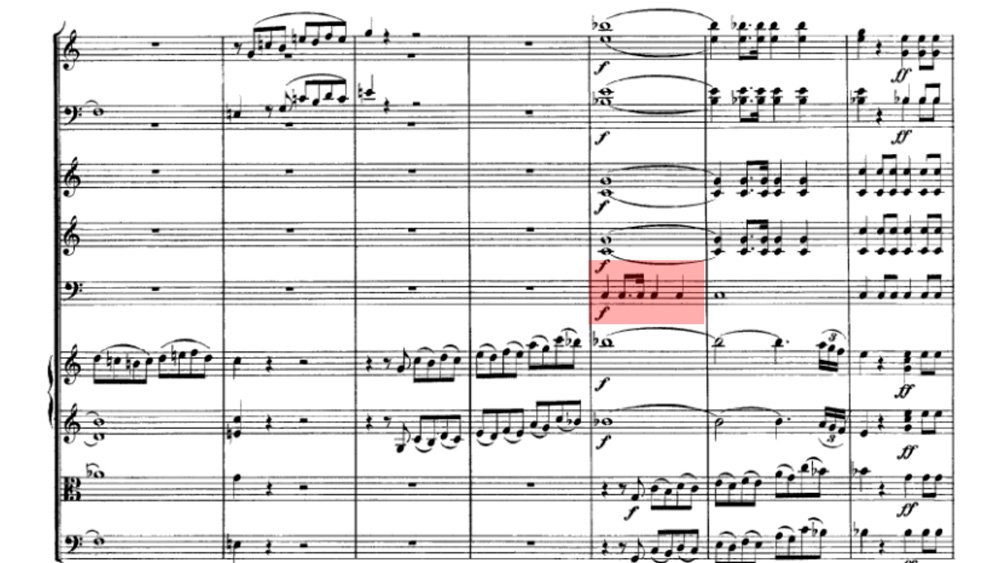

Here’s another surprise: the phrase closes in G major not really leading to anything, certainly not in the way we are used to in a sonata form. The stop-and-go tactic takes over in this part as well and instead of a cantabile second theme we are abruptly faced with strong E minor chords.

The answer is in G major and in a piano dynamic. The reiteration mirrors this sequence, starting in E minor in piano with the answer in forte

The end of the exposition is based, once again, on repeating models. At one point though, the music comes to a stop and changes direction or so it seems.

Mozart stops on the dominant of G and plays with the second degree of that scale, using the flat on the E to give more suspense to the line. It could be the beginning of the development, or a bridge to a third theme, or to the coda.

It’s the coda. The exposition ends on a motive we’ve already encountered used to bridge to both the repeat and the development

A brief interjection adds a bit of sadness cast away almost immediately with the bridge to the recapitulation.

Coda

The coda sees one last surprise: the same technique used in the development section is adopted here and we see the rising scale motive passed between the violins and the woodwinds, being disrupted, and transformed into a series of questions and answers till the end of the movement

Poco adagio

The second movement opens with a phrase that is quintessential Mozart: cantabile, broad, structurally perfect, logical and full of sentiment. With the typical rhythm of a siciliana – a genre often included in baroque works that reminds in its core rhythm of a slowed down tarantella.

Notice the game played between violins and horns with the latter answering with an arpeggio.

The descending figure of 32nd notes reminds the listener of the central part of the first phrase. Mozart moves on to a parenthesis in a dark C minor and back to the major scale. But look how he proceeds: the chromaticism of this section, which anticipates the Prague symphony, keeps the attention constantly up.

Imagine to be someone who listened to this for the first time in the 18th century. A lot of these harmonic ventures would capture your interest because you wouldn’t know where they would end up.

In this case, we end up on a safe C major in conclusion of the first part of the movement. The development begins with the head of the theme. Things move around, hinting towards a change of key, but we are back to C major

Repeated chords of the winds and timpani throw us in much darker place, incredibly dramatic.

A peculiarity of this movement is the presence of both trumpets and timpani, normally omitted in slow movements where the lyrical aspect is more emphasized. Mozart uses them to create a different sound, a different atmosphere from the one the regular listener of the time would be accustomed to

The development proceeds with a passage that to me sounds almost sarcastic, portrayed by the bassoon and the cellos and basses. After landing on an F minor, the same scale element is picked up by the violins and then further developed. Look at the bass line, moving up chromatically from Ab to C and picking up the scale again in the final part of this development

With a few minor changes, the recapitulation repeats the material of the exposition, finishing, this time, in F major.

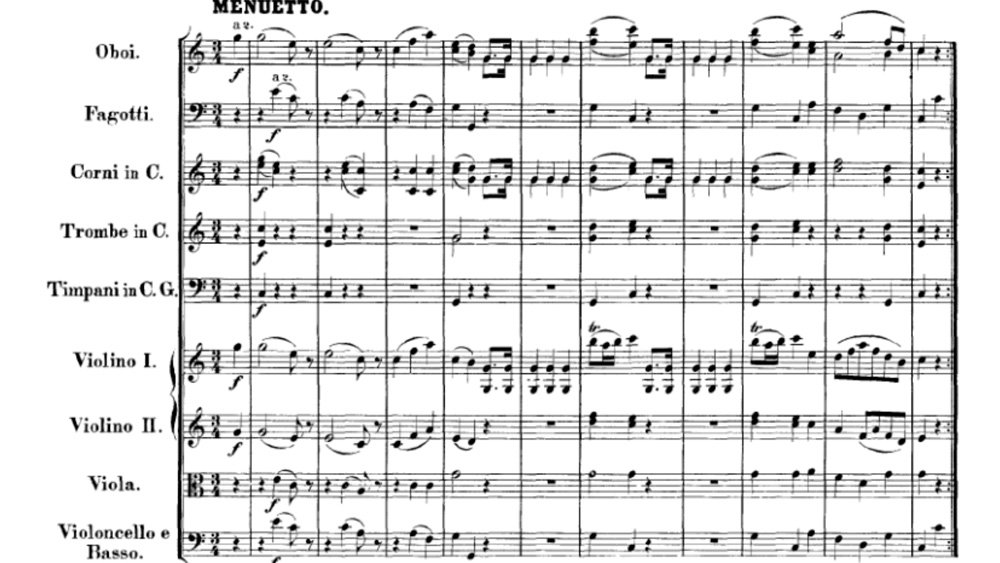

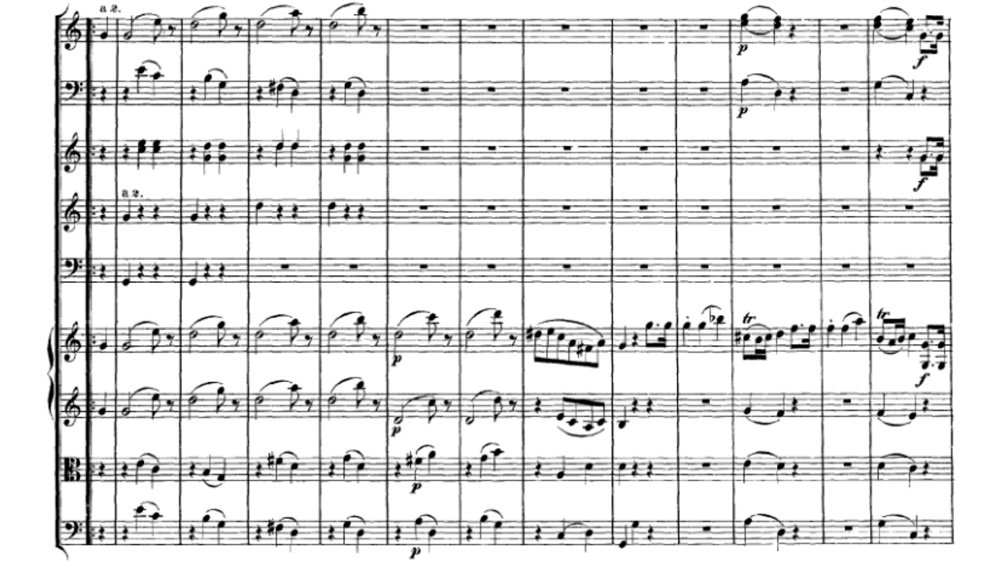

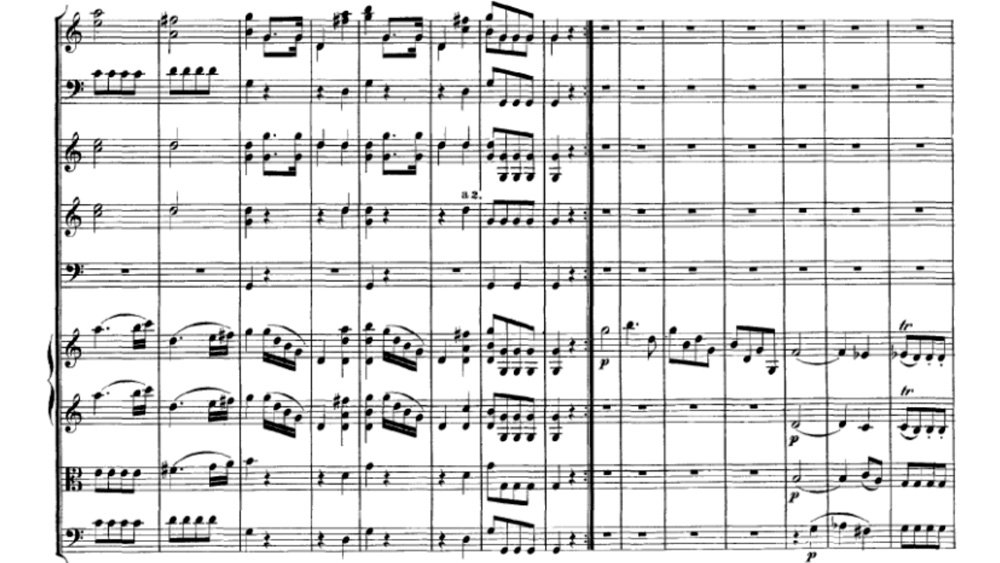

Menuetto

The classic third movement of a classical symphony: the courtly menuet. This one does have some of the features of the Laendler, a more rustic Austrian dance.

The menuet has a typical ABA structure. Each section is normally split into 2 parts.

Notice the presence of Mozart signature rhythm – here slightly variated – of which we talked about earlier.

The second phrase uses the same material reversing the direction. Where it was going down in the first phrase, here Mozart moves it up.

The rhythmic battle-like element is transformed within a softer frame and then returns in its original form while the head of the theme is used to close the A section

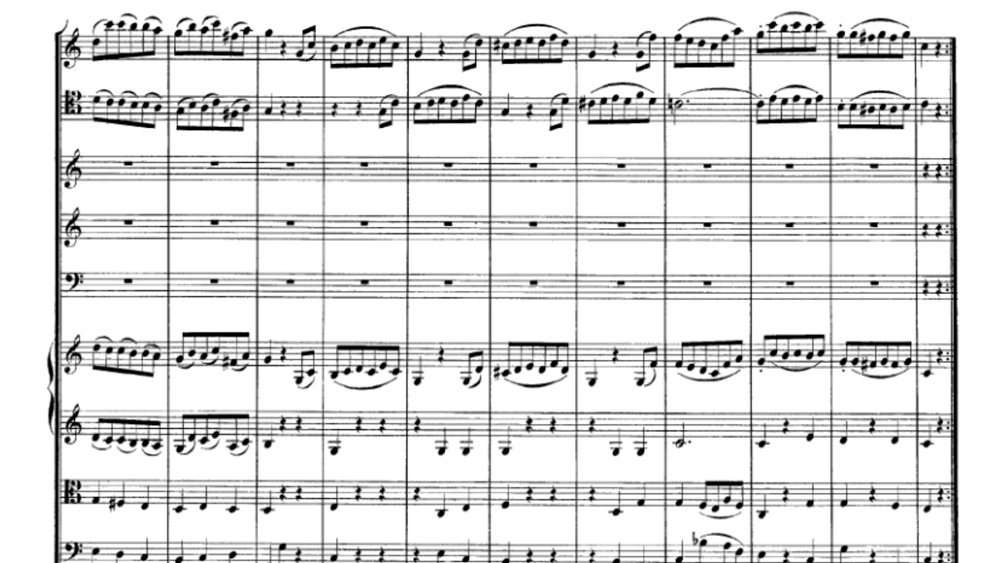

Trio

A traditionally mellower trio follows: the first part is a lyrical line, fairly rustic in its sound given by the couple first violins (in their very low register)-oboes

The answer is left to the violins and bassoons while the oboes conclude the phrase. The first phrase is retaken, with a small canon in the bassoon and the trio ends, prompting the repeat of the menuet

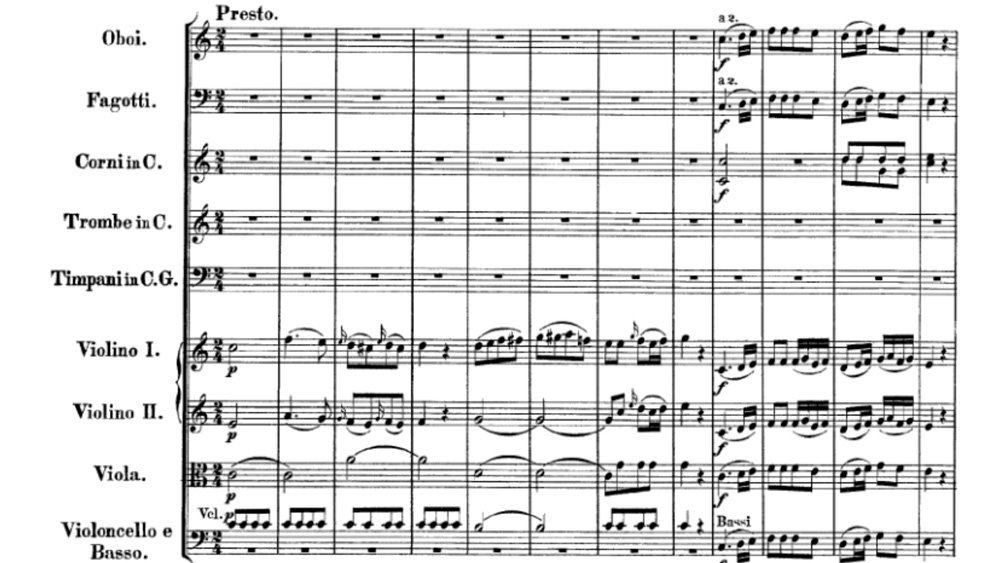

Presto

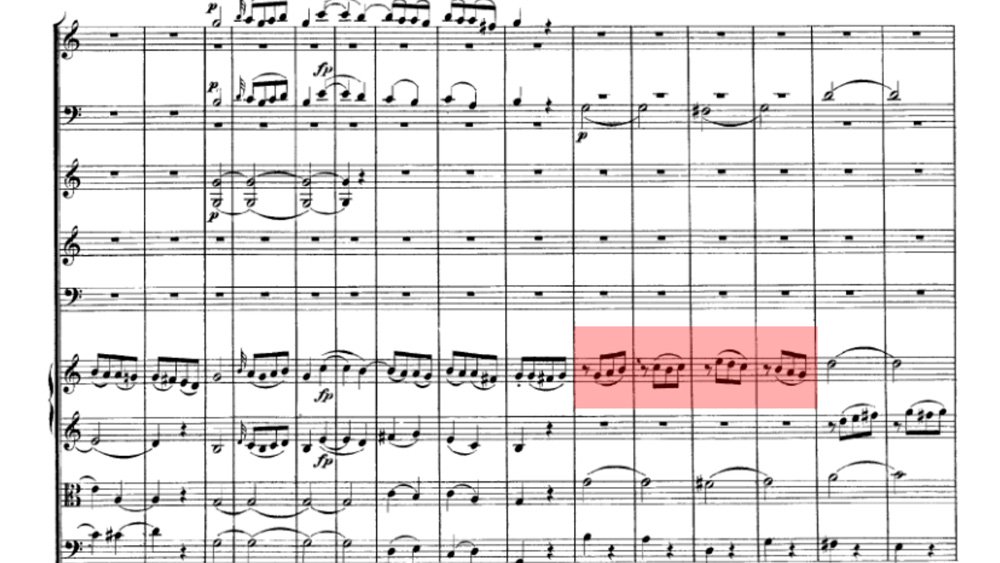

The last movement of this symphony is structured, again, in sonata form: an exposition with two more or less contrasting themes, a development where musical ideas get tossed around and reworked and a recapitulation.

The first theme makes use of lots of contrasts. The opening is all questions and answers. The violins gently ask a question and the orchestra firmly answers.

Could we be already at the second theme’s mark? Not yet. Mozart is being “spiritoso” as in the first moving, joking and playing with both music and listeners.

This is a small bridge, modulating to G major and introducing us to the second theme played by the violins in 6th and then by the woodwinds as well

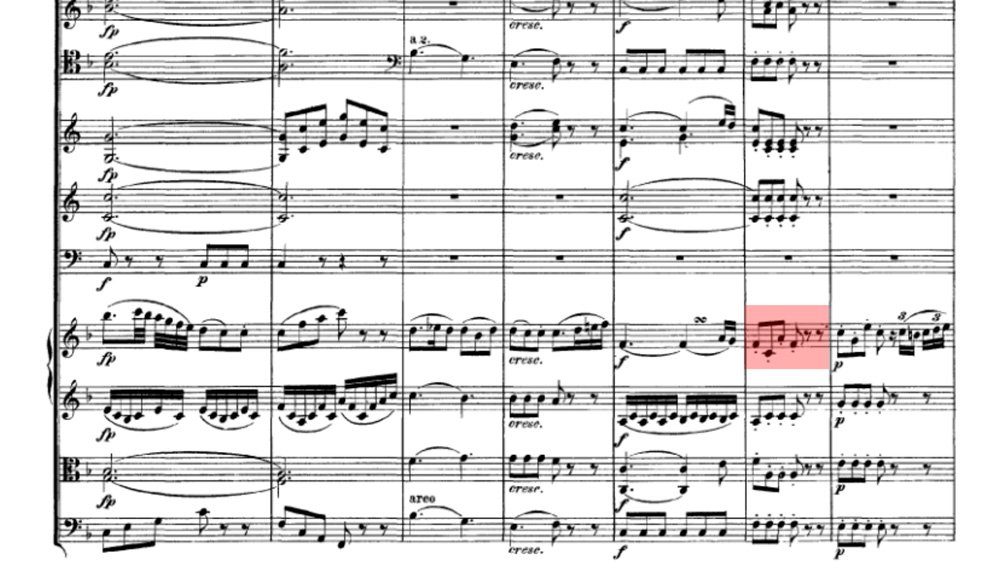

The end of the phrase gives us a 4 bars motive that Mozart masterfully transforms in a whole musical paragraph: it’s a very simple line, moving up and returning on its own steps.

We hear it first in the first violins, then it’s passed to the second, the violas, and the cellos and basses and then back to the violins, finishing the phrase in G major

This is what Mozart plays with for the entire development. The motive is passed in a progression back and forth from the violins to the basses and then to the bassoon and oboe. And the violas, and second violins, and first again, and so forth to the end of the development marked by a chromatic scale back into the recapitulation.

The recapitulation proceeds as usual and we only find a small variation in the coda, where an element is reiterated twice, increasing the excitement in anticipation to the conclusion of the symphony

Technical tip

Keep it small. And in one. If you really want to switch to 2, do it only for the wrist. The smaller and more compact your gestures are, the easier it is to keep the tempo effortlessly.

0 Comments