Introduction

A prominent figure in the Czech musical world, Josef Suk’s star has been unjustly declining over the years, something we’ve already seen happening to quite a few composers like Franz Schreker.

Suk grew up with music: his father taught him organ, piano and violin; he later perfected violin with another teacher on top of taking up composing.

Perhaps this is the most known aspect of his life. His composition mentor was none other than Antonin Dvořák. Moreover, Suk ended up marrying Dvořák’s daughter, Otilie, in 1898.

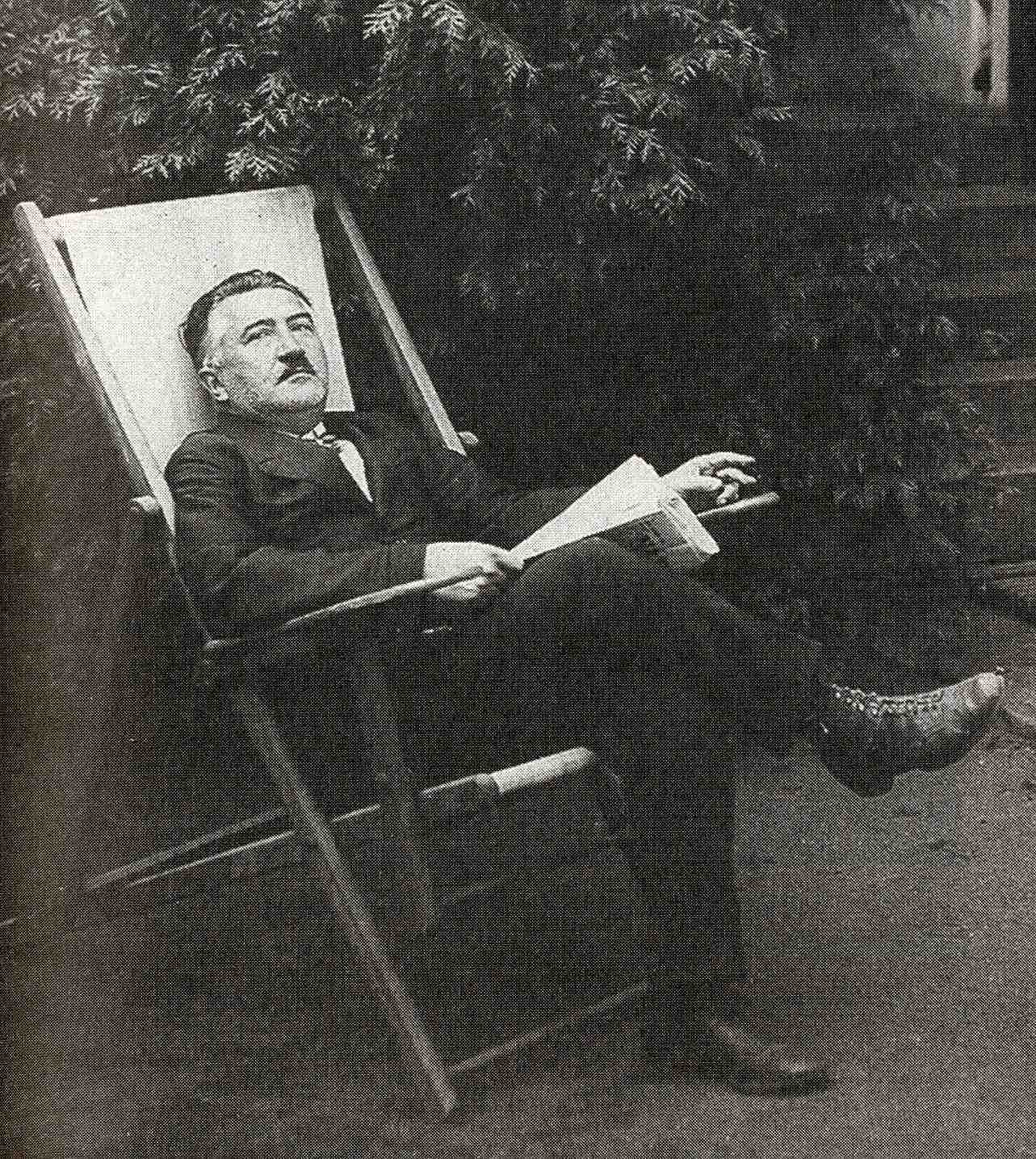

Josef Suk in a picture taken before 1930

Happiness did not last long as first Dvořák and then Otilie died. These events inspired Suk’s Asrael Symphony.

During his lifetime, already in the early years, Suk was admired for his abilities as a composer by many. Dvořák first and foremost but also the famous critic Eduard Hanslick and another composer who had a close relationship with Dvořák himself, Johannes Brahms.

Josef Suk – Serenade for strings op.6

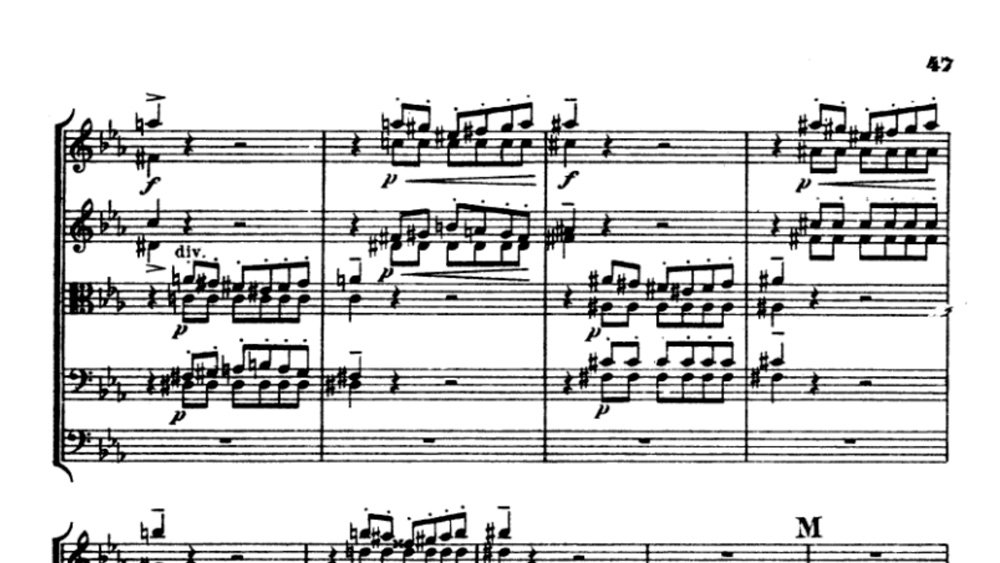

Should you need a score you can find one here.

The Serenade for Strings was written in 1892. After a partial premiere in 1893 and a full premiere in 1895, the work quickly became popular, and got the nice endorsement of Brahms.

It’s in 4 movements: Andante con moto, Allegro ma non troppo e grazioso, Adagio, Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo presto.

Andante con moto

A lovely nocturnal opening, very similar and not unexpectedly so, to Dvořák’s Serenade.

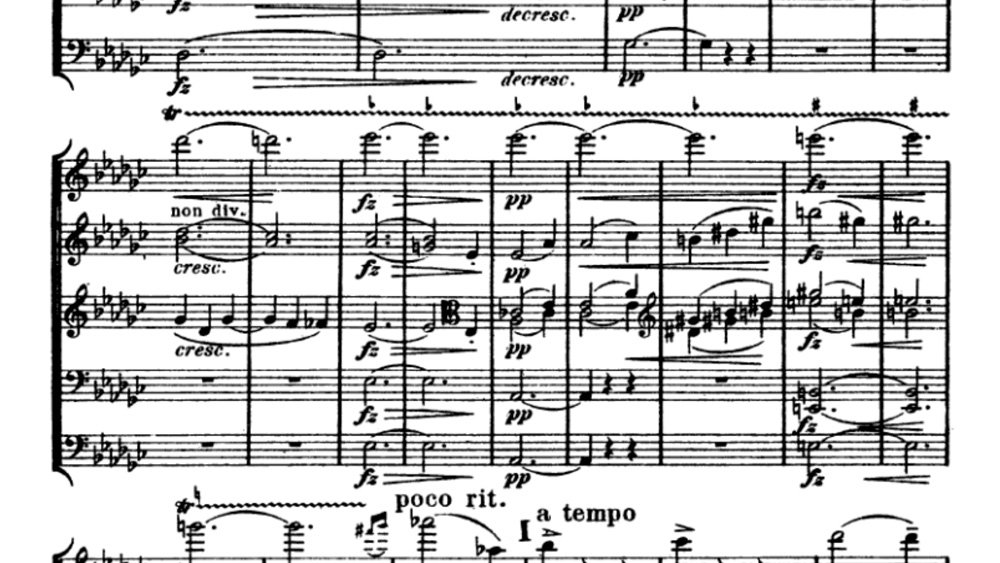

Second violins and violas are the motor pulsing underneath a delicate melody sung by the first violins. Cellos and basses punctuate with pizzicatos, like little drops of water in a pond.

The cellos join the first violins in the second part of the phrase and initiate the second phrase, taking up the role of the violins.

As you may have noticed, there is a typical romantic inclination to chromaticism, shifting the harmonic layers to change perspective.

One element is used to create a bridge which lands on the first theme again, in forte this time, played by the first violins an octave higher. The cellos imitate 2 quarter notes after the violins

This theme sees now some development, passing between violins and cellos, and reused in a more melancholic take by the second violins. The element that created the transition between the first and second theme is developed as well landing on the second theme once more and then used to bridge back to the first theme.

The arpeggio is disrupted and from the low register climbs all the way up. The head of the first theme is played by the violas, in their high register, in an ethereal atmosphere

Back to earth and its sorrows, and then to the first theme in B major. Shortly, we head for the coda which sees the return of harmonic games played on an Eb pedal of the basses.

The structure of this movement is not quite a complete sonata form: the development is nested into the second theme and everything is kept very compact, carefree.

Technical tip

Much like in the first movement of Dvořák’s serenade, this movement is about long legato strokes with inner pulses.

Registration is one of your best friends in this kind of music: try to follow the pitch contour with your hand. It’s an invaluable and very elegant way to break the pattern.

For a technical analysis take a look at this other video

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

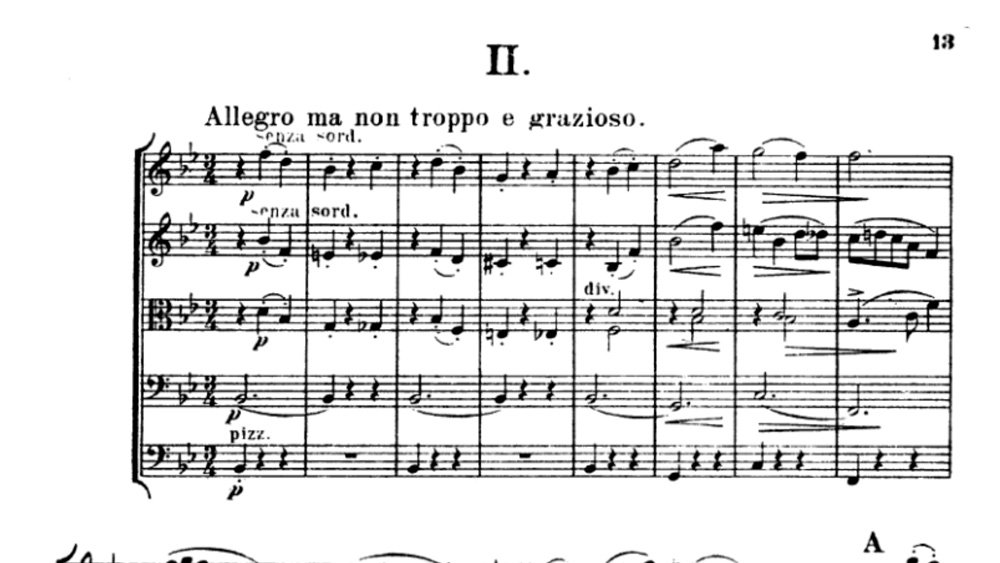

Allegro, ma non troppo e grazioso

We are moving to the dominant key of Bb, in a serene ¾. The simplicity and clarity with which the phrase is constructed remind of the classical era: an 8 bars phrase that can be split into 2 4 bars half phrases, which in turn can be split into 2 bars cells.

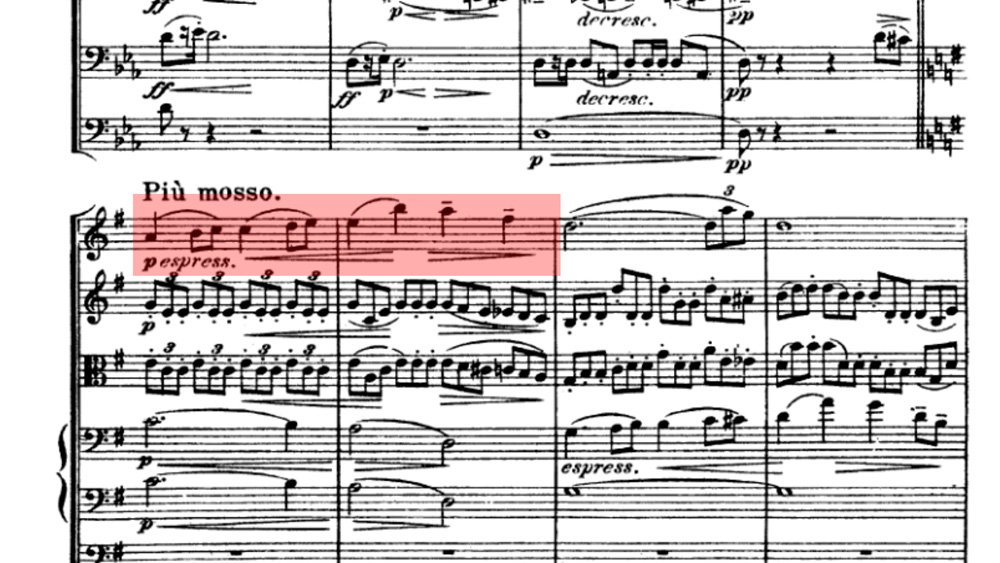

The phrase is repeated with some small variations and proceeds introducing an element typical of Czech music, found very often in Dvořák’s music as well: the hemiolas, or the displacement of the natural accent every 2 beats instead of 3.

The variation of the phrase includes a triplet, used to bridge to the return of the main theme, while the hemiolas put a stop to everything on a gran pausa – a bar of rest where everybody is silent. Again, the hemiolas rule in an unexpected Meno mosso which seems like the beginning of a new section but is, in fact, just a bridge.

The clouds of the Meno mosso dissipate quickly, the main theme returns, and leads us to the central part of this movement.

We land on a serene Gb major. Notice the rhythmical figures in response to the cantabile theme, another hommage from Suk to his mentor

With textbook compositional technique, Suk repeats the phrase and uses the material for the middle part of this section, landing on a variated version of the theme.

The texture thickens, with the second violins and violas taking the lead, but the first violins lighten the atmosphere with their trills in the high register

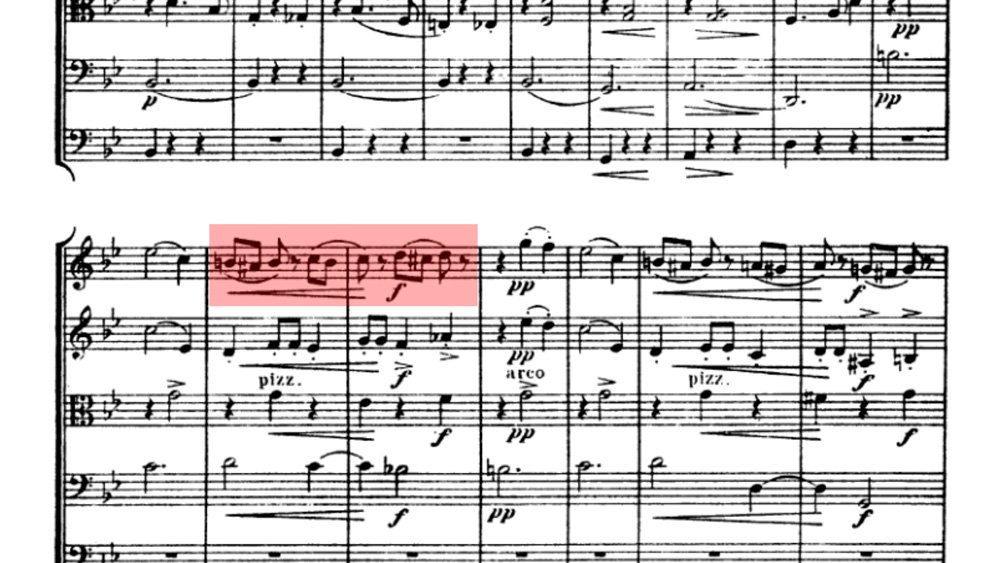

Suk takes a somewhat unexpected turn, developing the ideas into a passionate passage which eventually sees a citation of the first theme of the first movement at letter K while building a bridge to return to the first section of the piece.

Again, in quite an unexpected way: the tempo slows down, the orchestration is thickened by splitting almost every section into 2 distinct parts (see letter L) then thins out and abruptly changes to the Tempo primo where a dramatic bridge finally connects to the reprise

The first violins take the lead again and move up the phrase in the high register to calm down immediately, using the theme to close the section. Notice the 16th notes cells both appearing as a unifying factor.

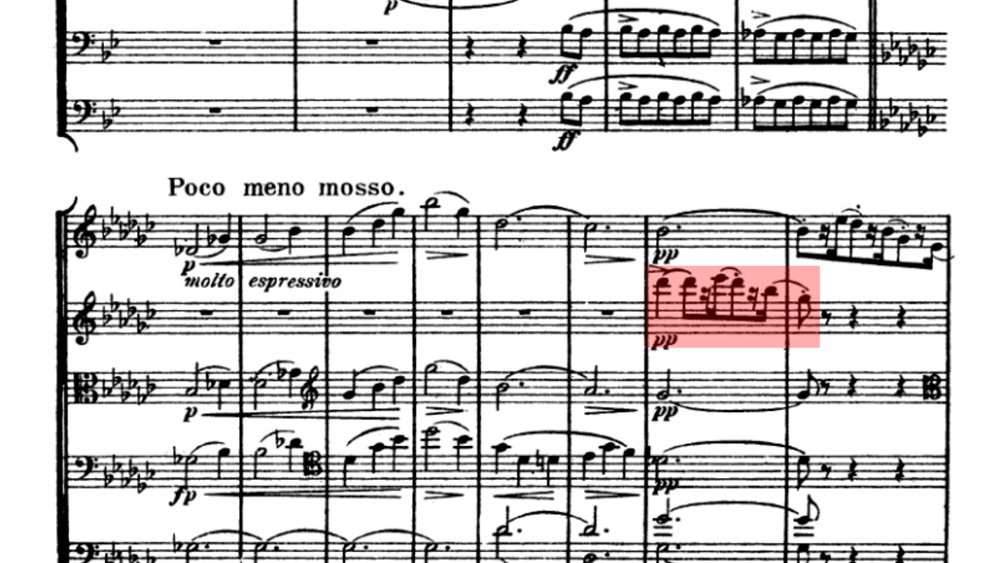

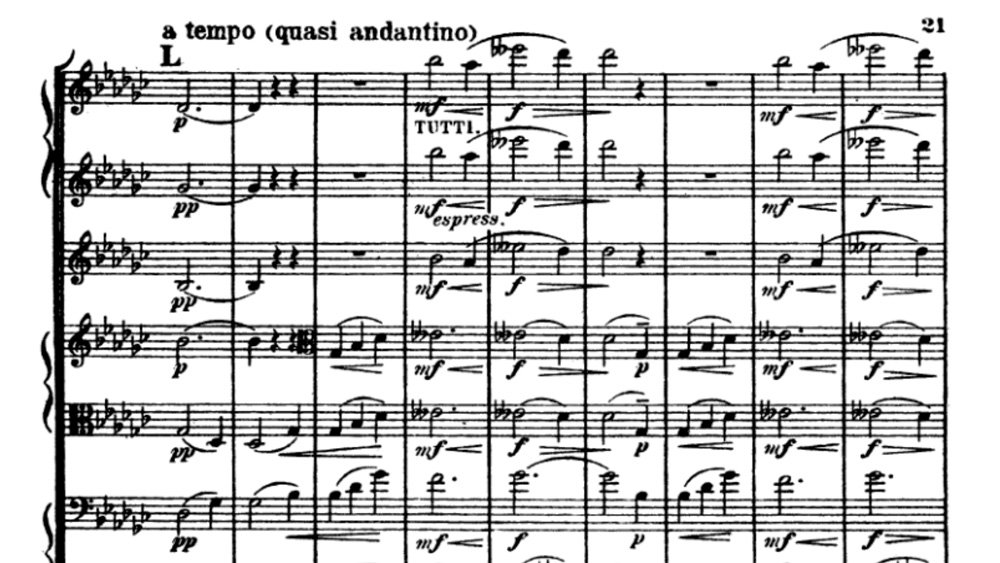

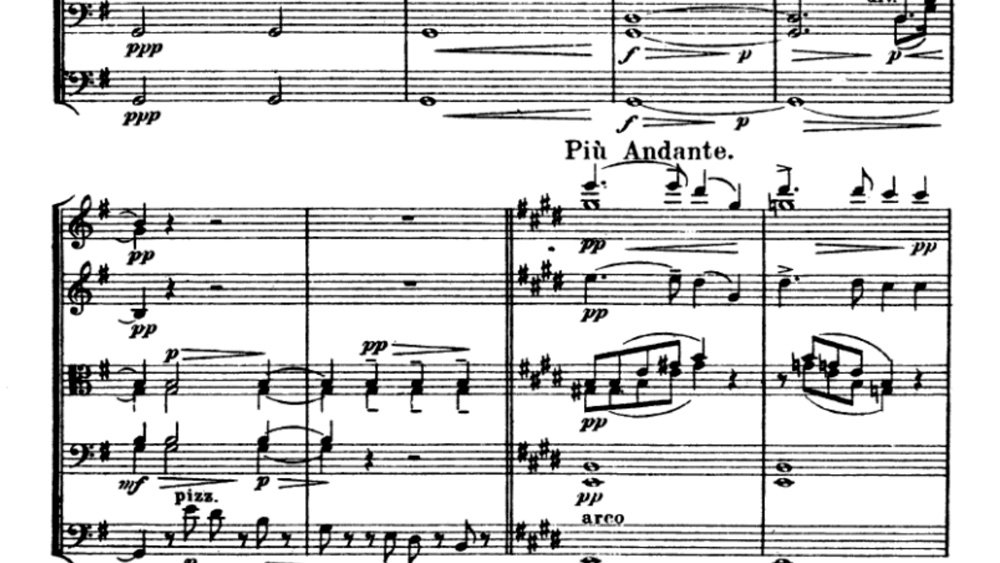

The phrase stretches its ending, closing in G major. But the very last resolution opens on a E major in the Più’ andante part. A new musical idea is presented by the violins and then taken by the violas. The accompaniment gradually intensifies, turned into triplets by the cellos. Again, almost every section at some point plays divisi, enriching the texture

The theme is passed to a solo violin and further on to the violas. Look how rich this page is: from letter F the triplets played by the violas and cellos add certain anxiety; but at letter G the feeling is different. While the violas sing the melody the cellos and violins exchange counterpoint lines of rare beauty.

We enter a new development part at letter H: the head of the theme is there but is used to build a model repeated throughout the next few bars. The triplets are also present, propelling the phrase forward

The roles are switched, with the cellos and violas taking over the melody while the violins accompany with triplets. The crescendo adds to the accelerando and canonically we would expect a big passionate explosion. Instead, the music folds back presenting the first theme’s elements in the first and second violins in an ethereal pianissimo bridging to the full reprise of the theme serving, in turn, to bridge to the coda

Technical tip

The biggest difficulty of this third movement is the spacing of the strokes. Feel the resistance of the sound on your hands or at the tip of the baton. Like going through water.

This will help you keep your strokes homogeneous, pulling the sound from one pulse to the other. Focus on the accompaniment rather than the solo.

For a technical analysis take a look at this other video

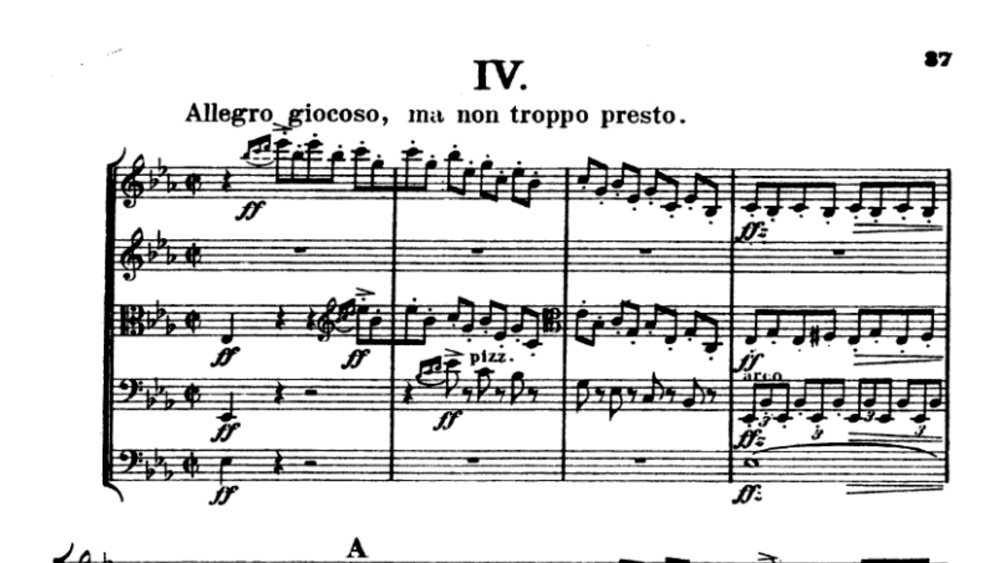

At the end of the phrase, 2 bars reaching to the playfulness of the introduction hand over the material to the first violins and a crescendo bridges to the theme played in fortissimo by the cellos and basses.

The playful aspect extends to the structure of the movement as well: after this bit of introduction and a clear first theme we might expect a cantabile second theme in classic sonata form structure. It’s not so. Suk uses more of a free form here, introducing new motives, and constantly elaborating the musical material. From now on it’s a sort of constant development section all the way to the coda.

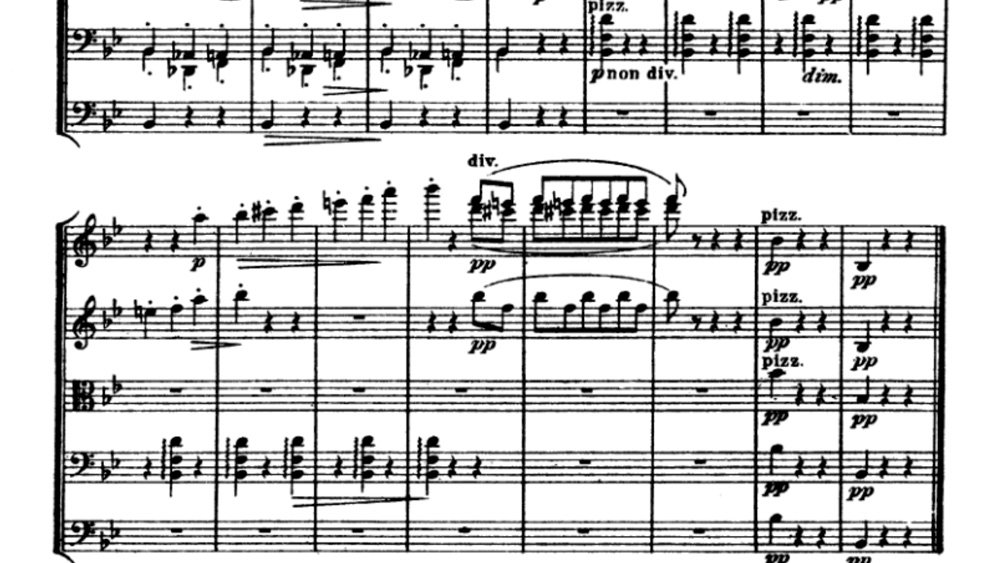

Notice the rhythmic diminution 2 bars before letter D: the cellos play triplets of 8th notes, then naturally create a rallentando effect by turning them into triplets of quarter notes. These become at letter D a syncopated motive, which will return time and again till the end of the movement. Notice also the ongoing presence of the short eight notes, another element that pervades the entire movement.

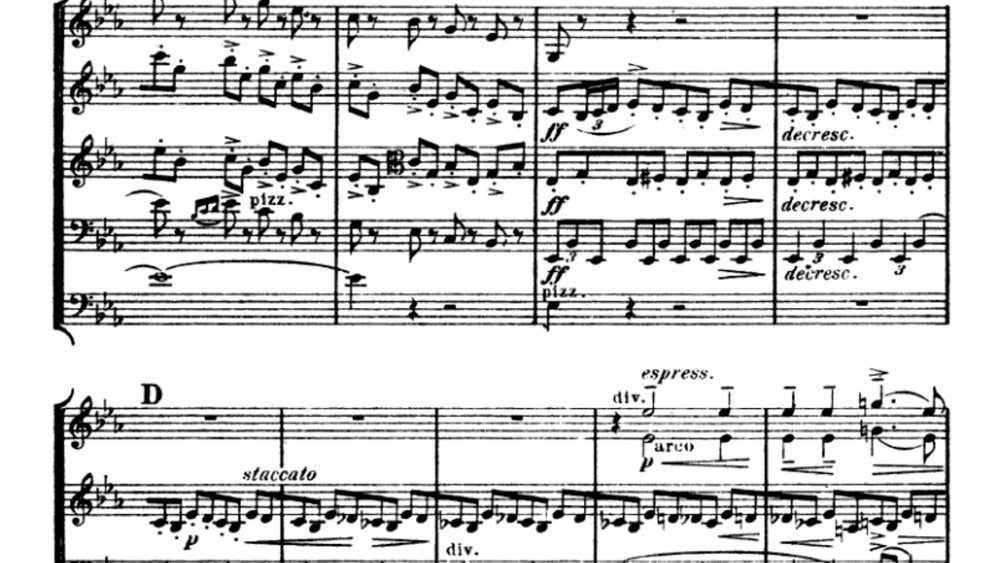

Those same eight notes serve as a connecting tissue to the next part, at letter F, where the first violins take the lead, again with a syncopated motive.

Roles are swapped and while the motive goes to the cellos, the eight notes are shared between first and second violins.

The excitement grows and grows, hinting towards a big explosion. But Suk changes direction, surprising the listener: the first syncopated theme is expanded in a Meno mosso section. Everything calms down.

The eight notes element is integrated into the texture. The playful element of the introduction and the main theme return, opening a long development.

The theme goes under traditional harmonic changes. Notice how the eight notes are ever-present in this part, to the point where they take over, in a dialogue between first-second violins and violas-cellos, all in divisi

The second syncopated motive shows up, in a canon-type game played by the cellos and first violins till its time for the main theme to interact with it. The Tempo I sees the return of the first syncopated motive.

We would expect a recapitulation here perhaps. Instead, the motive is elaborated and eventually lands on the first theme of the very first movement. This circular technique is something we’ve observed already in Elgar’s serenade for example, in Tchaikovsky’s, and, of course, in Dvořák’s serenade.

0 Comments