Portrait of Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy (1791)

Royal College of Music Museum of Instruments

Introduction

The “father of the symphony“, as Haydn is nicknamed, completed this particular work in 1787: it’s not a symphony with a title – like the “Drumroll” or the “Clock” – and it does not belong to a bigger series like the London symphonies.

It did become, however, incredibly popular and well-rooted in the repertoire. It holds, in fact, the wittiness, the humour, the elegance of the classical period perfectly nested into an almost mathematical construct.

Joseph Haydn – An analysis of the 1st movement of his symphony n.88

Exposition

In case you don’t have it at hand, here’s a quick link to the score.

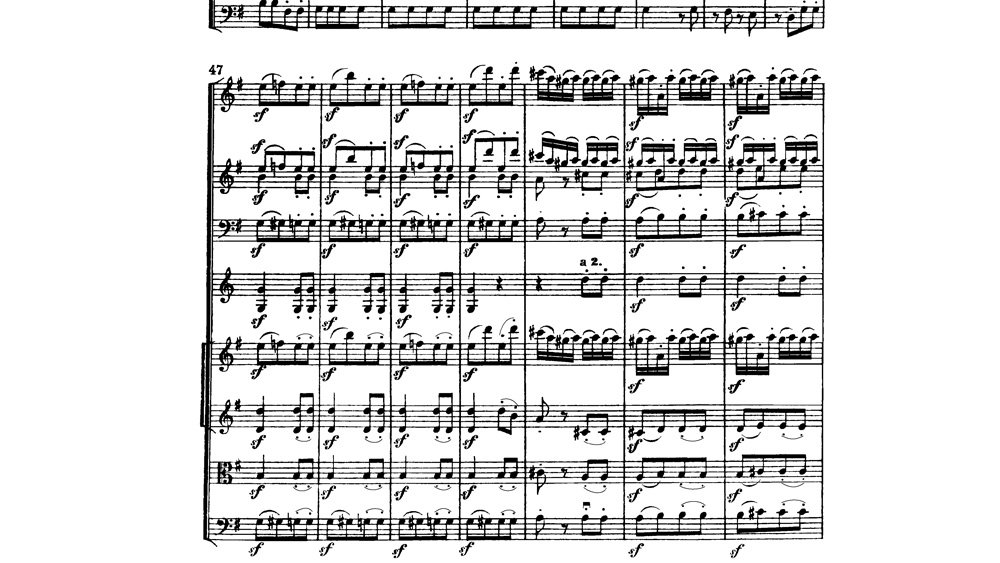

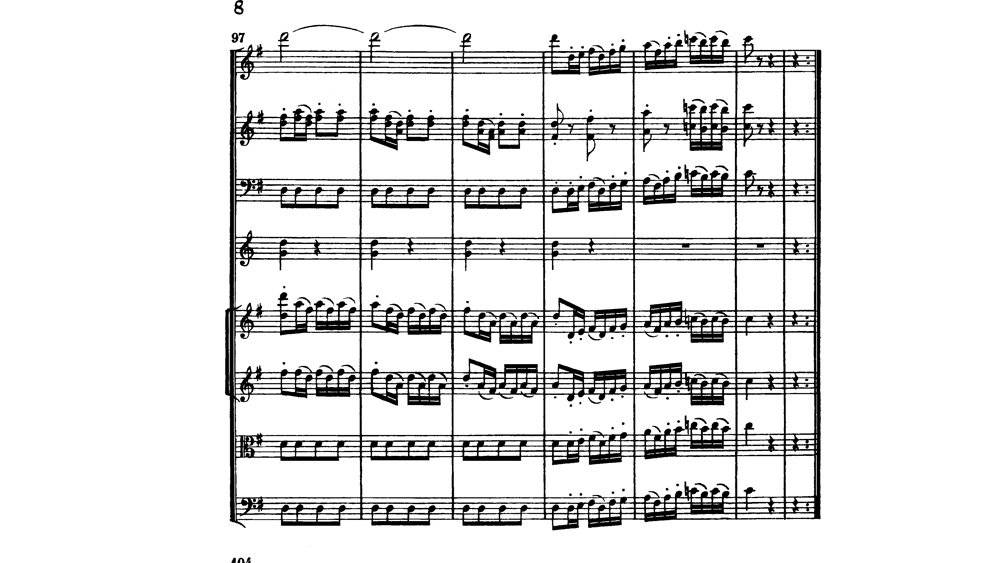

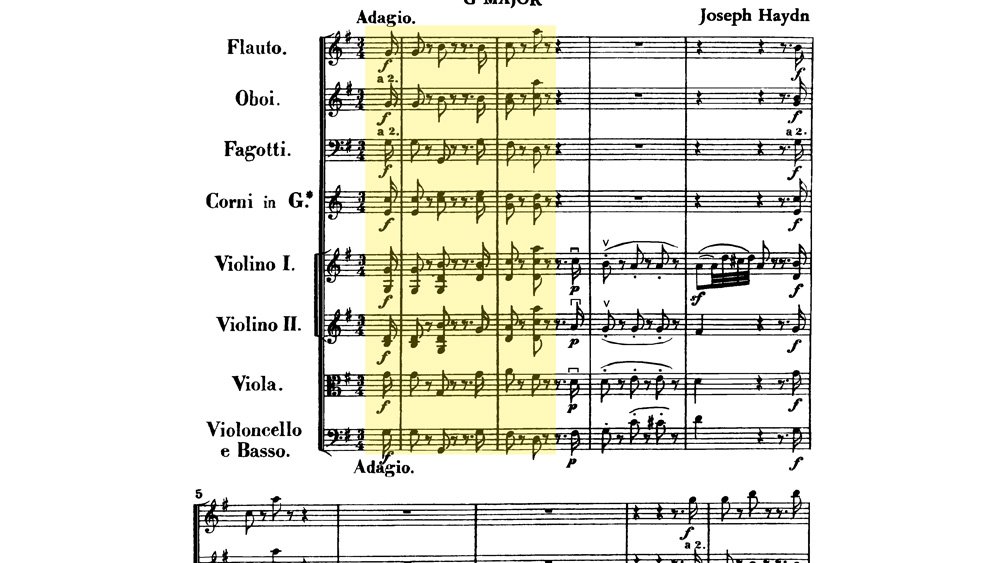

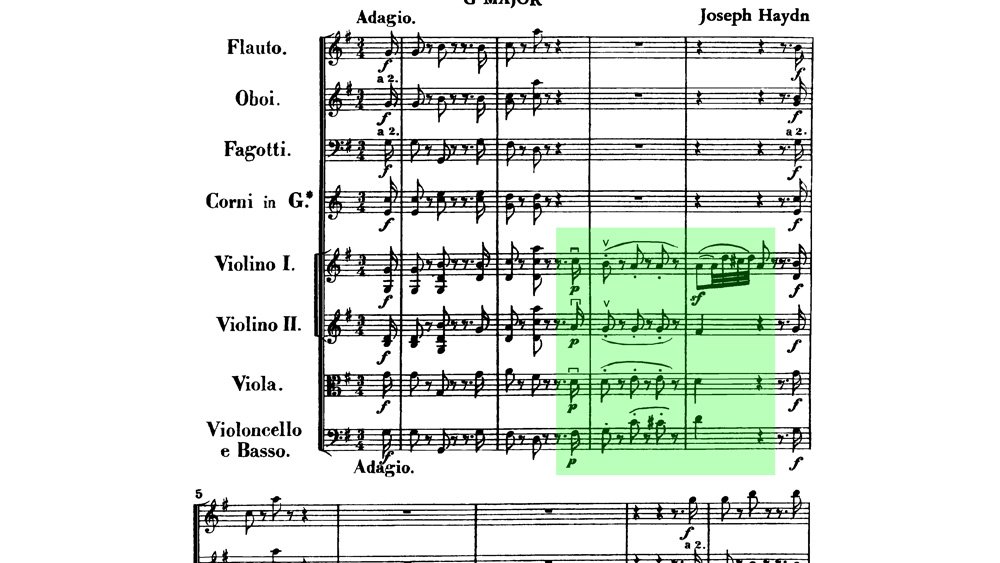

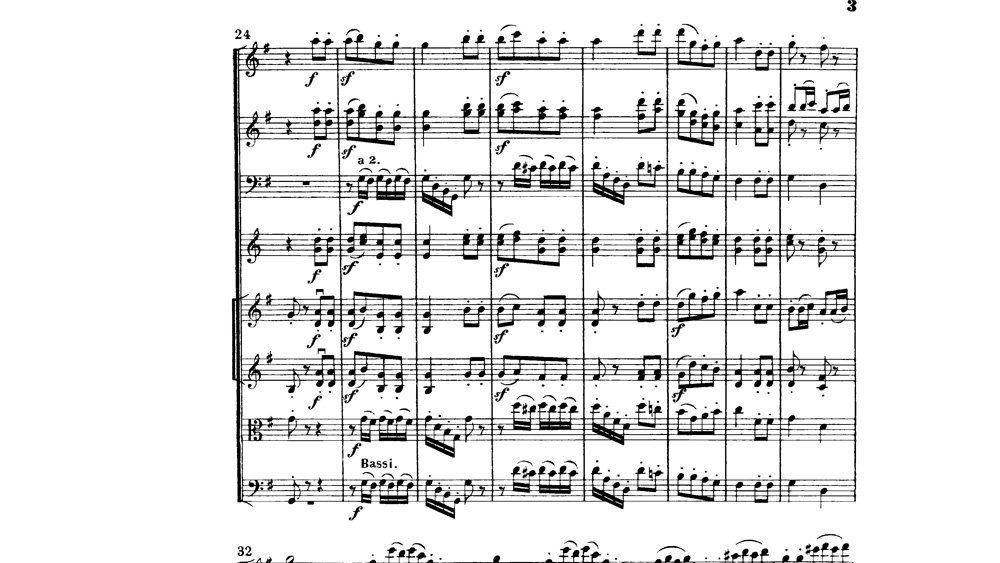

The first movement begins with a short introduction, quickly settling on the dominant to prepare for the Allegro. The strings open the Allegro, with the main theme, and the rest of the movement develops from here. The form is a monothematic sonata form like we’ve seen in Haydn’s symphony n.104; both the exposition and the development make use of a single melodic idea.

Haydn opens the Adagio with a 4 bars phrase split in 2: a forte question

Naturally, we land on the dominant. The question is reiterated, shortened, while the answer is expanded. All in all, in perfect classical era balance, we end up with 8 bars.

Haydn proceeds to a repeat of the first phrase, or so it seems initially.

The chords model is instead repeated three times. The answer is, once more, a model based on the first answer repeated 3 times.

We have a total of 6 bars now. But the phrase needs to finish: hence the last 2 bars, on a pure dominant chord, bring the number of bars back to 8.

Technical tip

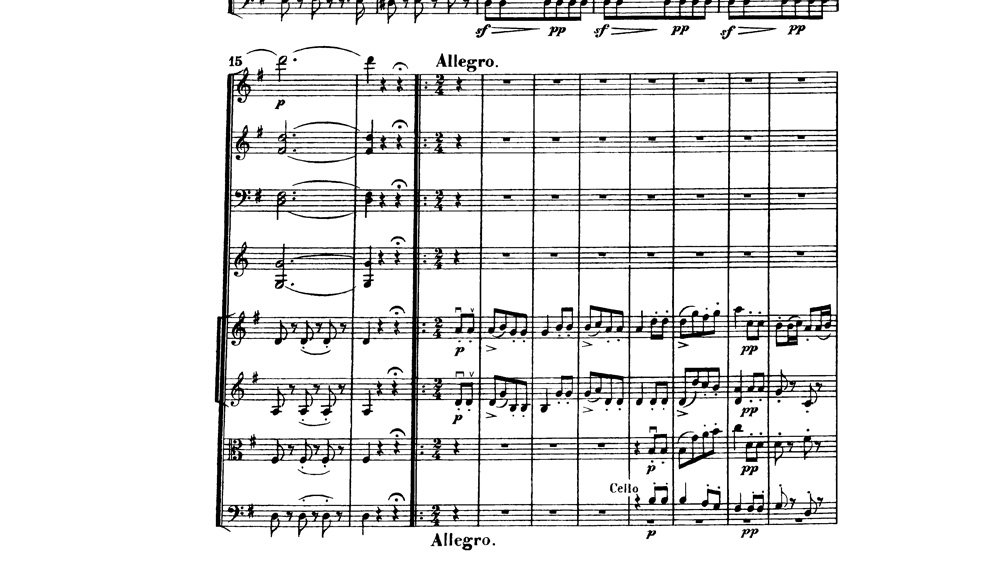

The first musical choice you have to make lies in the tempo: is it in 3 or in 3 subdivided? The choice you make will inform your technique. There is one common denominator between the two: the pulse before the 16th notes is essential in both cases.

For a full technical analysis, look up the video in the repertoire section

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

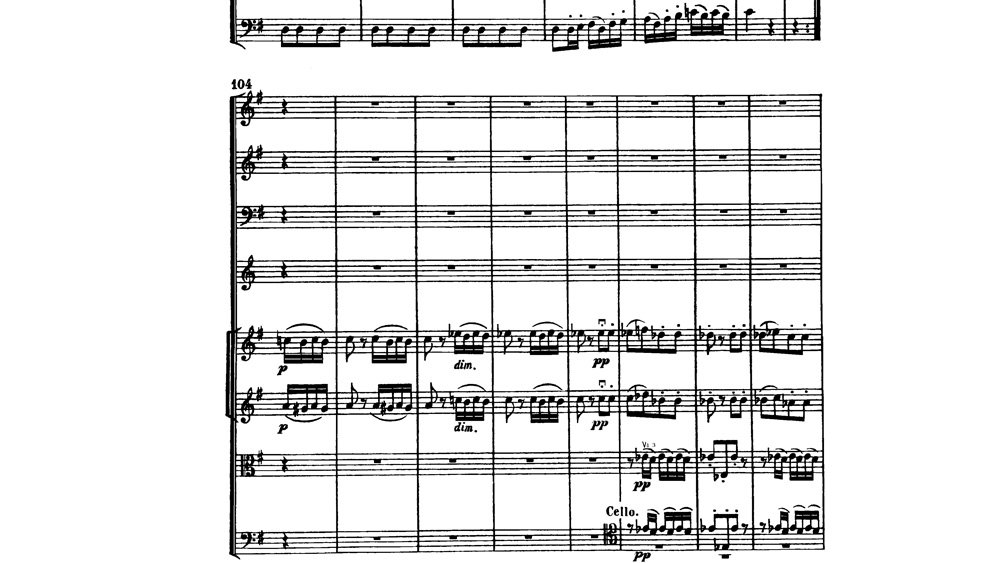

Notice the 16th notes figure in the bass line: it’s carved out of the 16th notes figure appearing on bar 23, reversed.

The following phrase expands on the idea, transforming them into an arpeggio. But the really interesting thing is one of the bass lines: the harmony goes back and forth between the home key of G major and its dominant seventh. While that is perfectly normal, a little less obvious is the pedal of G held by the cellos and basses, also evident in the first eight note of the bassoons‘ line.

We would expect a modulation to D at some point here, and the entrance of the second theme. But the bubbles continue to burst and in the following phrase, we’re still in G major.

Haydn reintroduces the rhythmical idea of the theme and we finally transition to the key of the dominant

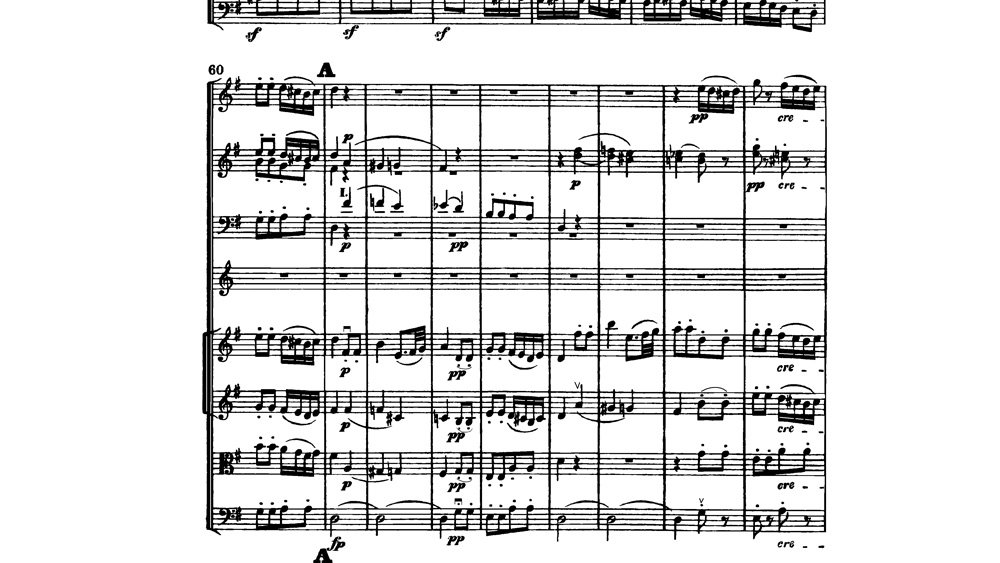

Letter A is where the second theme would be in a regular sonata form: one bar before A we would be on an A major chord, and A would expose a cantabile theme in D major. Not so in this case. As mentioned, this is a monothematic sonata form. Letter A has the flavor of a coda, with a lovely chromatism

but it is, in fact, “just” another episode. Repeated, with a variation, on bar 77, and taking the opposite direction 4 bars later.

Haydn throws us in the mix of a battle between the low and high register parts of the orchestra, with the same idea bouncing back and forth multiple times

before ending the exposition on a suspension

Development

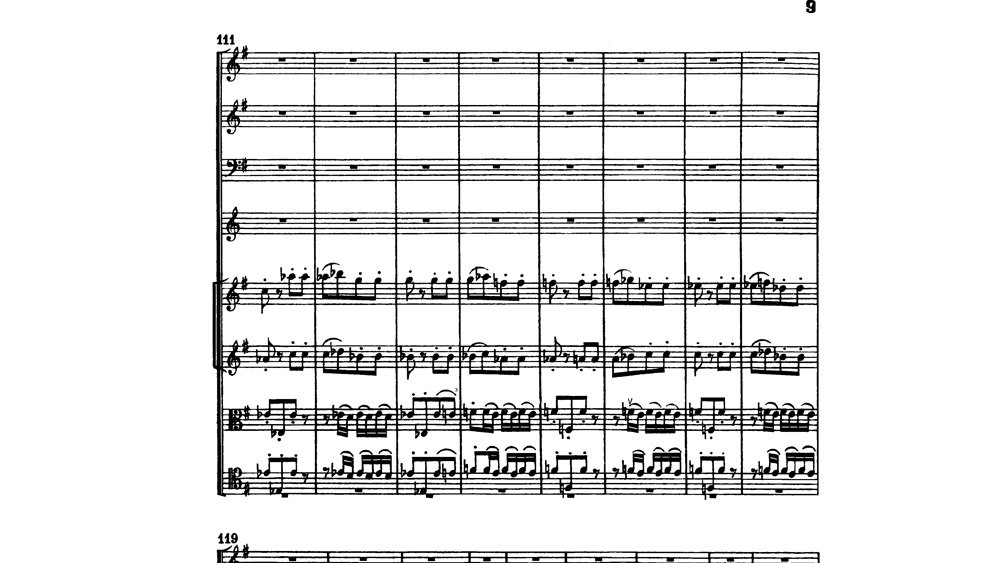

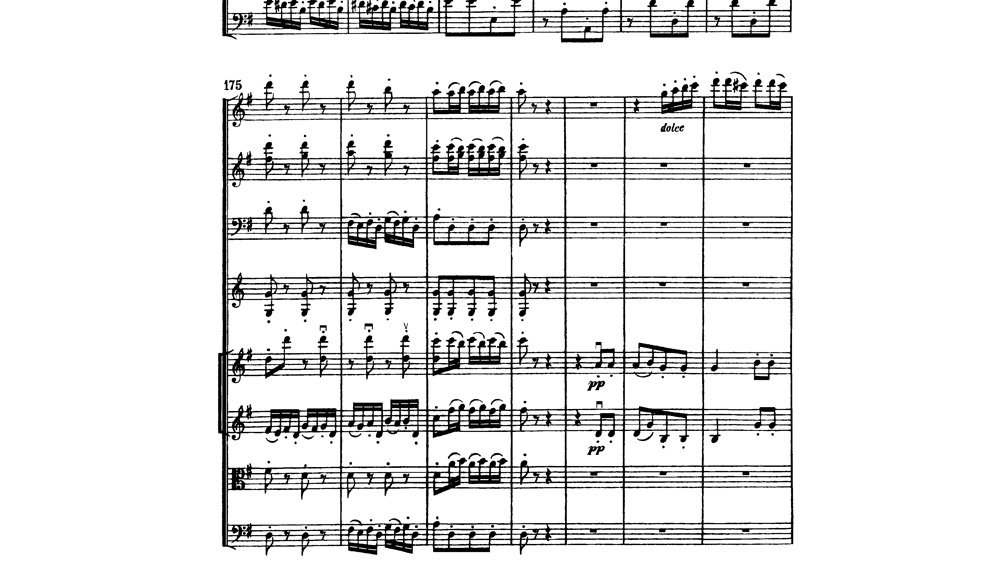

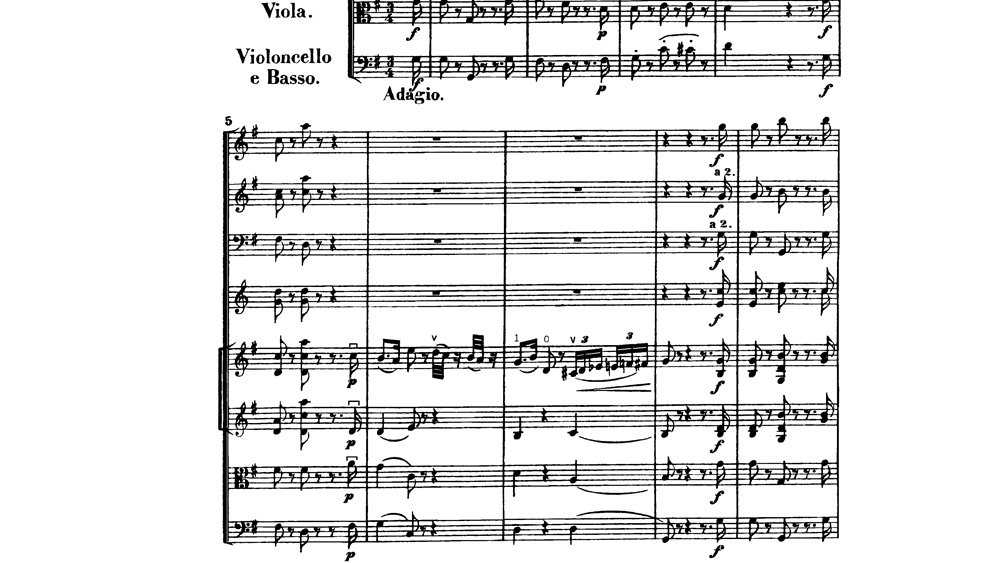

After the repetition of the Allegro, we enter the development right away. Those 16th notes, repeated in a quadruplet now, introduce us to a kaleidoscope of changes and transformations

The main theme is, of course, the core element. Right away it gets underlined by the 16th notes figure, exploring different keys.

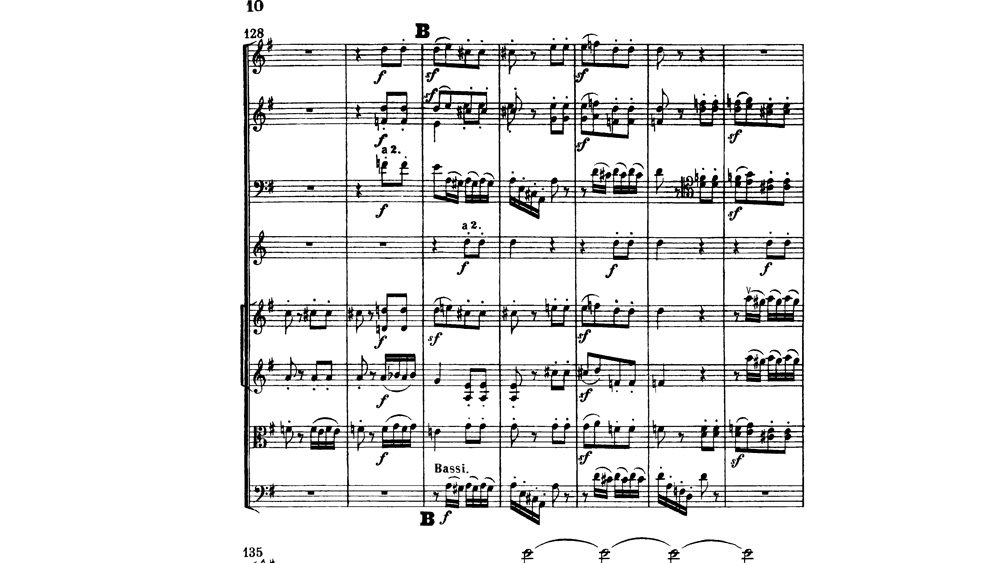

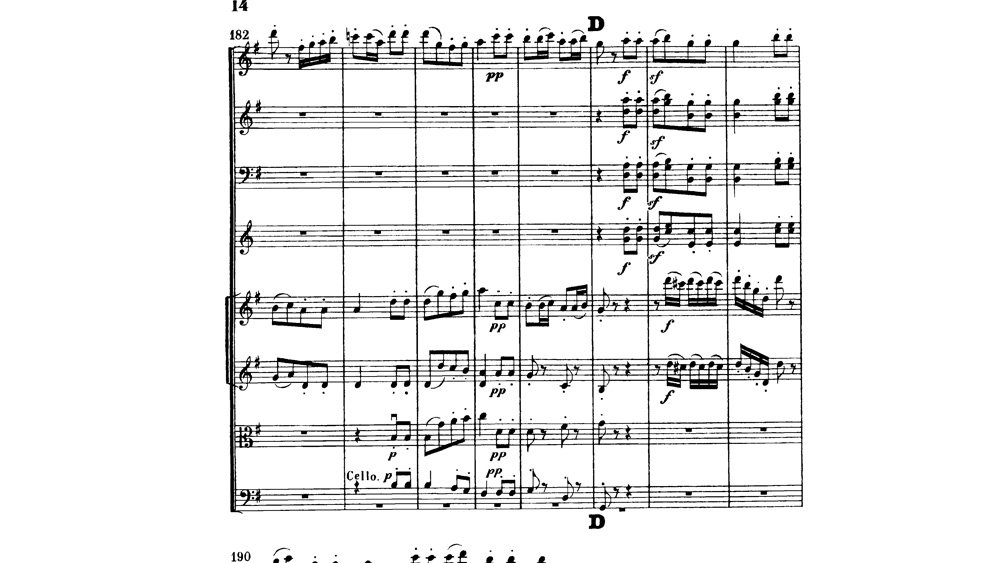

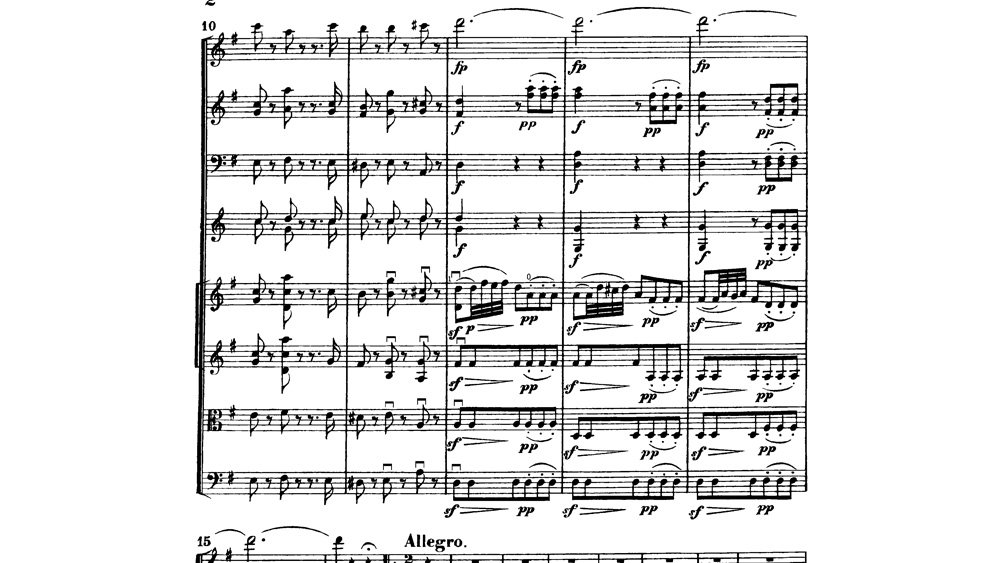

Notice how everything remains in the piano and pianissimo range all the way until letter B. The pickup to B marks the entrance of the rest of the orchestra and the increase of the drama

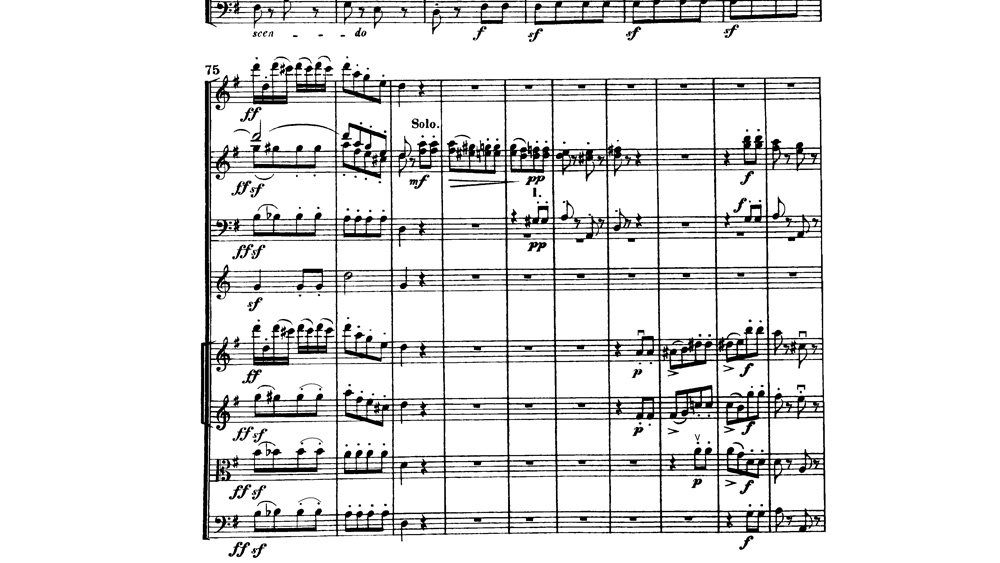

Everything is derived from the main theme: all of its element overlap and combine with one another, even dove-tailing each other like in this passage

The development ends with an episode we encountered at the end of the expositions, once again ending on the suspensive feeling of the dominant seventh leading right into the recapitulation.

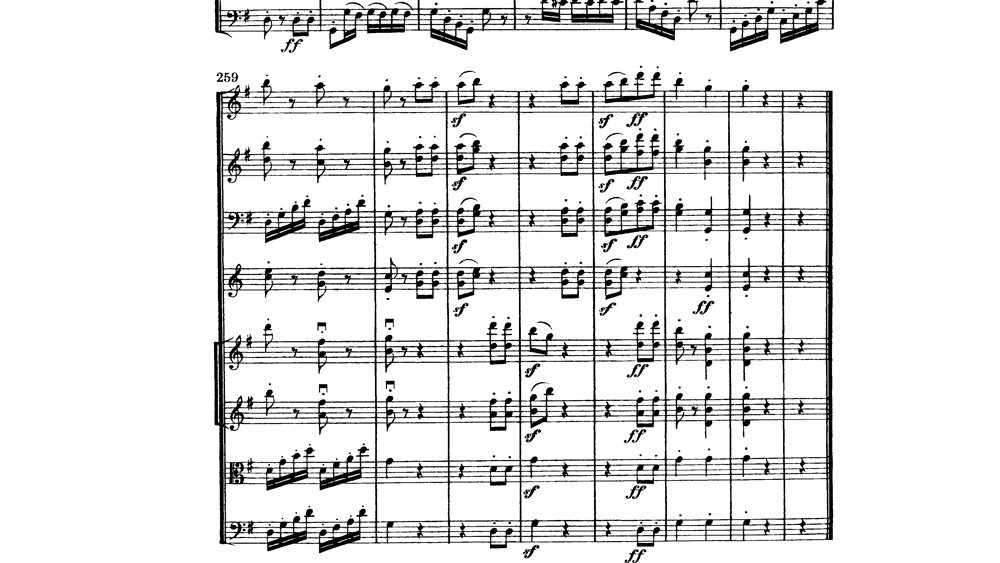

Recapitulation and coda

Notice the lovely addendum of the flute as a counterline. Using what? The same 16th notes we’ve seen so much of

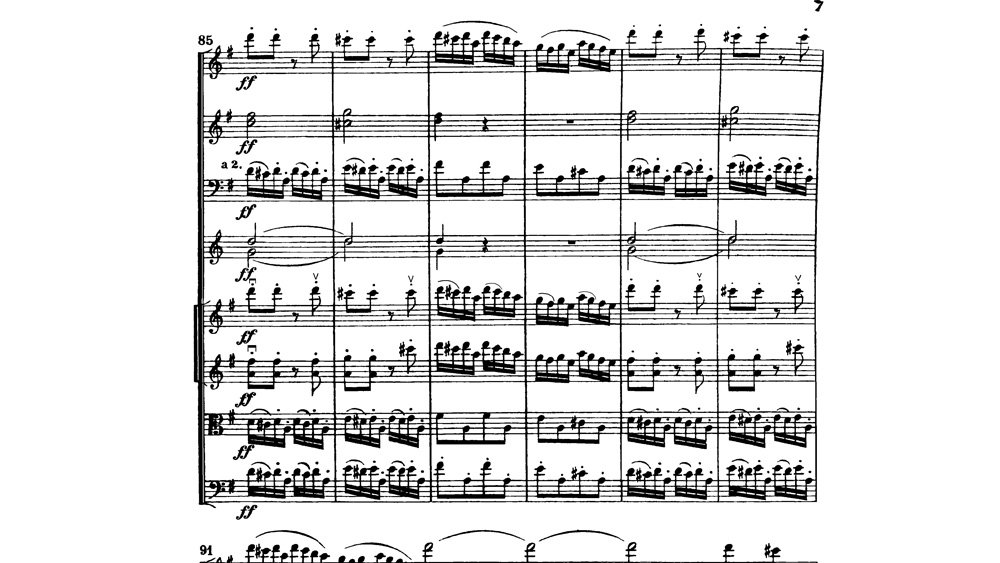

The rest of the recapitulation proceeds as usual, till the coda stresses one last time the main idea, with sforzato markings within a fortissimo dynamic. The last bars present the head of the theme split in perfect half, the ultimate question and answer

In conclusion

As much as it is not easy to write a symphony with 2 or 3 themes, it is even more difficult to keep the attention of the listener when there is only one of them. As we’ve seen here, Haydn is a master in putting the same material through different transformations.

The tough part is now left for the interpreters: finding a balance in bringing out the details without sounding pedantic or losing the overall picture is no small task.

0 Comments